CPO Shuhaily Zain: Beyond Mere Enforcement of the Law (Part One)

By Dato’ Dr. Ooi Kee Beng

PENANG PROFILE

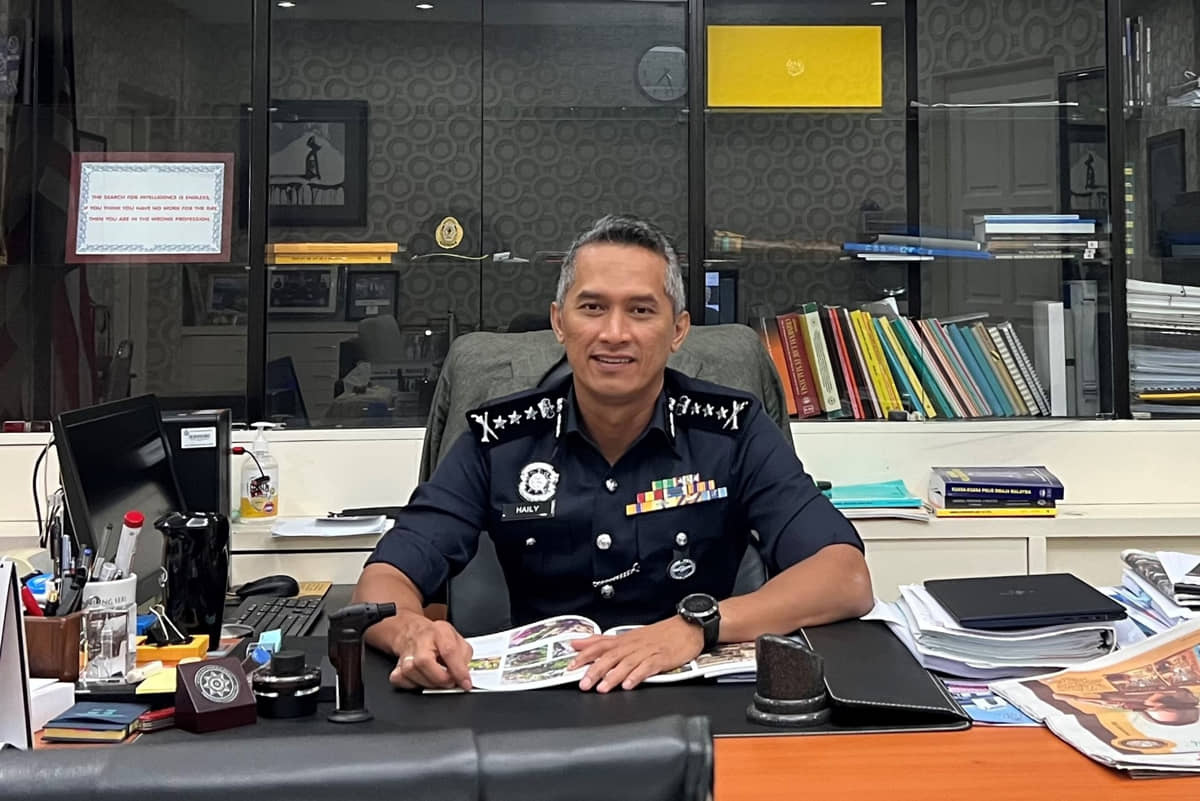

Ooi Kee Beng in conversation with CPO Shuhaily Zain

DATO' MOHD SHUHAILY ZAIN became Penang's Chief Police Officer (CPO) during the Covid-19 pandemic. He was quickly recognised locally as a dynamic leader who is highly conscious of the important role in social development that the police has, or should have. Penang Monthly editor, Dato' Dr. Ooi Kee Beng, interviews Shuhaily at the Penang Contingent Police Headquarters on his journey to becoming Penang's top cop.

OOI KEE BENG: Dato' Shuhaily, you were appointed CPO of Penang in July 2021, and by all accounts, have had a strong positive impact on the Police Department within a short period. So, we would very much like our readers to have a chance to get to know you.

MOHD SHUHAILY MOHD ZAIN: Let me start with my background then. I was born on 12 July 1972 in KL. My late father was a policeman, and since my wife’s father was also a cop, my children, besides having a policeman for a father, has grandparents on both sides who were also in the [police] Force.

OKB: Any chance of them becoming cops as well?

SZ: [laughs] So far, I don’t see any inclination in them in that direction. So, on my side, I think I’ll be the last one in the family to be a cop—unless they marry a cop.

My dad was a traffic policeman in KL. Through the years, he really slogged: he put in the hours to improve himself. Gradually, he became an officer. So, he went from the bottom to the top. In fact, he headed the traffic department in Penang.

OKB: Were you living in Penang then?

SZ: Back then, I had just graduated, so I remained in KL. His legacy is the one-way streets in Penang; he initiated that work. Though in the beginning, he was criticised from left and right, from the Consumers' Association of Penang (CAP) and other parties. That resilience was something I always admired about my old man—Mohd Zain Ismail.

We are five siblings. I’m the eldest. The next son studied in Ireland and came back as a doctor; the third studied in Wales and is now an engineer with Bernama. My sister was a housewife but now runs her own business. My youngest brother is in video production.

OKB: So, you're the only one who didn’t go into the private sector.

SZ: I did, initially. I was with Sime Darby for one year, and then I hopped on to the futures market. I was in the bourse for about seven months before the market collapsed in 1997. I was lucky in the sense that one of my bosses, a Boston graduate, advised me early that a last-in-first-out policy would be implemented by the company, and that I should find something stable, or things could get very difficult for me in the years ahead, especially since I was still a fresh graduate. Fortunately, or unfortunately, there was a job open for Cadet ASP (assistant superintendents). So, I applied, got in, and went for training for the next nine months.

OKB: What’s your academic background, Dato’?

SZ: Right after high school—I studied at Methodist Boys’ School in KL—I went to UIA, Universiti Islam Antarabangsa. I was doing English, but I didn’t fit in well enough, and I hopped over to International Relations. I was lucky that my dean and lecturer back then was Dr. Ahmet Davutoglu, who eventually became Prime Minister of Turkey (2014 to 2016). He really opened my eyes to how the world works when he taught me Post-Soviet Politics and International Political Economy.

Then I joined the Force and was selected for the Special Branch.

Those were my foundation years in the Force. In 2001, I decided to go for a peacekeeping mission in Kosovo for 18 months. I was one of the youngest allowed to go on that kind of mission. Things were raw there, very basic.

The fact that many Albanians had lived in other European countries during the Soviet era and had returned to help build their nation, only to be told that they need to follow instead of taking the driver's seat is an eye-opener for me. And I think that through them, I also came to more properly understand the meaning of independence.

I dwelt with the locals, and eventually spoke Albanian a bit. Unfortunately, four or five months before I left, the country was in a bit of a havoc because the Albanians felt that they were not treated fairly by the United Nations Mission. So, the country fell back into clashes but, this time with UN personnel.

It was where I learned what the struggle for independence is about. Our youths should understand that what we have today is due to sacrifices made by earlier generations. Every year, we celebrate Hari Merdeka, but I think our understanding of Merdeka is quite superficial. Our schools should reemphasise history more creatively to make it more interesting and better appreciated.

I went through two winters there. The first winter was horrible. You had electricity for four hours, and then for eight or 10 hours, you had no access. So if you wanted to cook anything, you better do that within those four hours. And the winter was very, very extreme.

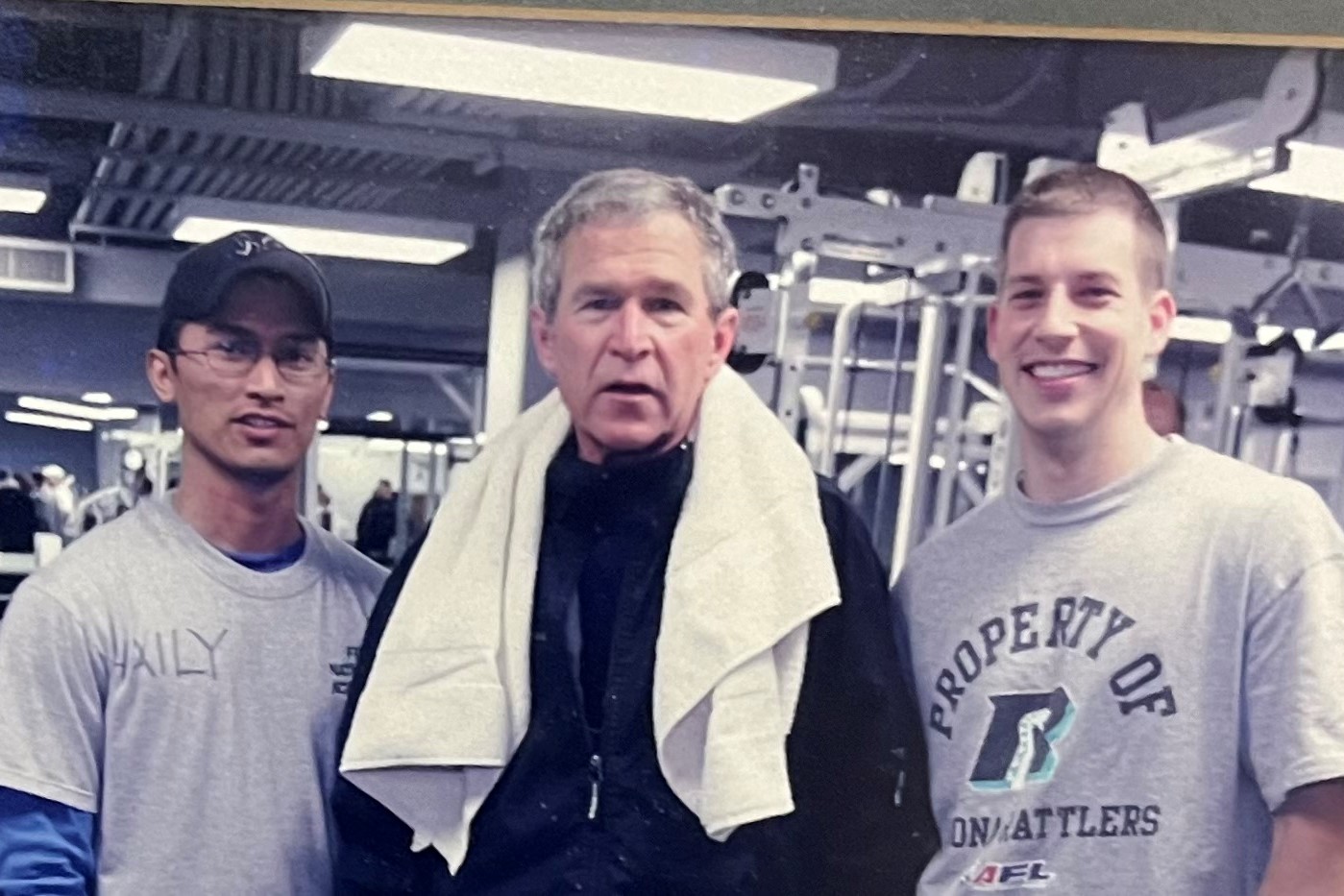

I came back in 2002 and worked at the foreign desk, after which I was sent for three months to the US for a course at the FBI National Academy.

OKB: Were you still with the Special Branch then?

SZ: On volunteering for Kosovo, I had been transferred to the administration department. I know there is a stigma about Special Branch people - of them being spies. But we are not James Bond you know [laughs], not at all. There was a lot of paperwork, really—reading and analysing. But that’s also where I learned to forecast and such stuff.

The three months in Quantico, Virginia introduced me to modern policing, to scientific investigations and digital technologies. I saw how meticulous, how professional they are — the pride, the training. Also, the realism. They are willing to spend; they invest in technology and in their staff.

There is a unit called the Behavioral Science Unit. If you have watched the series, Hannibal, you would see how criminals are profiled. That was where I learned how the policeman, the academician and the professional can work together. The Bureau is merely the investigator. Whenever they need scientific help, they will go to the universities and bring these people down on the ground to assist them in analysing the crime scene. That optimises their professionalism. I tried to emulate that here, with USM (Universiti Sains Malaysia).

OKB: How do you do that?

SZ: It’s not in terms of investigation. Instead, we asked them to assist us in impact studies of things that we are doing on the ground, and then to provide us with third-party, neutral data. Professor Dato’ Dr. P. Sundramoorthy (School of Social Sciences, USM) is helping us in a few initiatives. That's what I'm trying to do on that front.

In fact, I brought my officers to visit the factories to try to open up their minds to working with the private sector. They must understand what can be shared and what can't. The common goal is to encourage teaming. The factories that I’ve visited are all very open and very welcoming of ideas. That’s why I enjoy Penang. In fact, there’s a lot more that I can do, if time permits. The state government has been very helpful and open as well with me: they have assisted me a lot, and I want to chart my course forward from that.

Anyway, after my return from the States, I was sent to Singapore for a year and a bit to do my Master's. In the Force, I was actually the first candidate to be sent there to study. I suppose I was available back then - being unmarried and having no commitments. So, I did my MA in terrorism studies there and learned a lot about the counter-insurgency records kept in Singapore.

Again, it was eye-opening for me how much they know of Malaysian history and about the Emergency.

As far as career path is concerned and to summarise it, I spent seven years as Assistant Superintendent of Police (which is like Captain), and then seven years as Deputy Superintendent of Police (Major). It then took me three years to make Superintendent (Lieutenant Colonel), during which I was selected to be Police Attaché at our embassy in Washington DC in 2010, where I also became Assistant Commissioner of Police (Full Colonel).

Upon coming back after three years there, I was tasked with follow-up operations in Sabah's post-incursion investigation.

OKB: Oh, just after the incursion in 2013?

SZ: Yes, for secondary operations and stuff like that. I was involved in that until the IGP decided to take me out from Special Branch to become OCPD Hilir Perak instead. So, I was in Teluk Intan for 19 months (2014 to 2016) before being promoted to Head of Special Branch in Pahang. After 18 months in that position, I was called back to Bukit Aman to the Operations and Support Team there for four years before being posted to Penang as CPO in 2021.

OKB: You have only been here a year and a half, and I hear rumours that we might lose you soon, to Bukit Aman.

SZ: [laughs] Personally, I am not looking forward to going back. I’m happy where I am, and I think I can contribute a lot more here.

OKB: Things are more concrete here, at ground level, I suppose?

SZ: Exactly. Yeah. I like that. I like to be on the ground.

OKB: But can you skip or delay a promotion?

SZ: I have rejected a promotion once before. So that’s not something new to me. I knew I was moving up too fast, and there were more senior people that could be given the position. But it was left vacant for nine months after that, so in the end I had to take it. If I didn’t move, then nobody could take my position.

I was the youngest in many of the positions I filled. I don't know what I did, but God has made it easy for me.

OKB: You must have kept someone higher up impressed. To be sure, throughout your career, you have been very exposed to a lot of different experiences, and you attended many unique courses.

SZ: I have been lucky. I had bosses who guided me so very well—Indian officers, Chinese officers, Malay officers. In the Force, we are colour blind - brothers regardless of race or religion. My house used to celebrate Hari Raya, Deepavali and Chinese New Year. So, I’ve been very exposed to all races. That was already the case at Methodist Boys’ School and I think that’s what made me who I am today.

When I am here, I am here. I have never, in my career, thought about what’s next. I seek to fill my time with experiences that I can gain from. Then I move on. My bosses used to tell me that being a boss is not about getting promoted. It’s about your officers getting acknowledgment and getting promoted - that you produce good officers is an indirect recognition of your leadership.

OKB: That’s a very good ideology for leadership.

SZ: Indirectly, it pays off for me too, because my bosses then decided to give me more and more chances to lead.

I came from a very ordinary family. My dad struggled to bring up the family, and Mom helped him a lot. She was a housewife but always had small enterprises like jual nasi lemak to help my dad financially. My late father was in Psukan Polis Hutan (PPH) during the second phase of the Emergency, so, at an early age, I saw officers getting injured, coming out from the jungle having lost limbs and so on. I saw how the wives sacrificed while the husbands were in the jungle. So, I understand how important esprit de corps and such ideals are.

OKB: When did you first meet your wife, Ennie Salina?

SZ: I met her after I came back from Kosovo and started my family at the age of 35. My wife was actually my gym instructor. Now she happily instructs my life [laughs]. She is also with the government, with the Ministry of International Trade and Investment; she is a negotiator for RCEP. This means that, at home, we sometimes discuss international relations; she from the economic side and I from the political side.

I do find an understanding of history, be it individual or national, to be very important. You know, I bring my officers to visit the Peranakan Museum, for example. I tell them, you have to understand history to understand people - their way of life, their cultures... I love to go down to the ground, and associate with people and understand them.

I don't think making arrests is problem-solving. For instance, during the previous election, I think we managed things very creatively here. We met up with all sides, and things went very smoothly.

I tell my officers that we are dealing with problems that started a long time ago; we are seeing only the end results of the socialisation process. Those who commit crimes are often people who cannot live with the norms we take for granted, so they move out of it. It’s all about policies, in the end.

My officers are beginning to understand that we tend to get too engrossed in completing our investigation papers, in order to prosecute and for justice to be served.

But knowing the cause of a crime can be an important input to policymakers: “This is the outcome of your policymaking, and this is the remedy."

But no such process is in place yet.

[… to be continued]

Dato’ Dr. Ooi Kee Beng

is the Executive Director of Penang Institute. His recent books include The Eurasian Core and its Edges: Dialogues with Wang Gungwu on the History of the World (ISEAS 2016). Homepage: wikibeng.com