The TVET Landscape and Its Development in Malaysia

By Ong Wooi Leng

PENANG ECONOMIC INDICATOR

TECHNICAL AND VOCATIONAL Education and Training (TVET) is the main driving force for the socio-economic development of the country, helping ease youth unemployment while meeting industrialisation needs. Given this fact, and in the context of Industry 4.0, attention is required about metaverse technology being the current apogee of the virtual world, which should be incorporated into the country’s vocational training programmes.

According to Ramlee Mustapha, a Professor in Technical and Vocational Education at Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris (UPSI), metaverse learning dispenses with the expensive equipment many TVET courses require, such as CNC machines, automotive training and welding equipment.[1] It is also crucial to Malaysia’s TVET education remaining relevant in the near future.

Malaysia’s TVET Ecosystem

Malaysia’s first TVET institution was formed in 1964 by the Ministry of Youth and Sports and the Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR) through Institut Latihan Belia Negara (ILBN) and Institut Latihan Perindustrian (ILP) respectively.

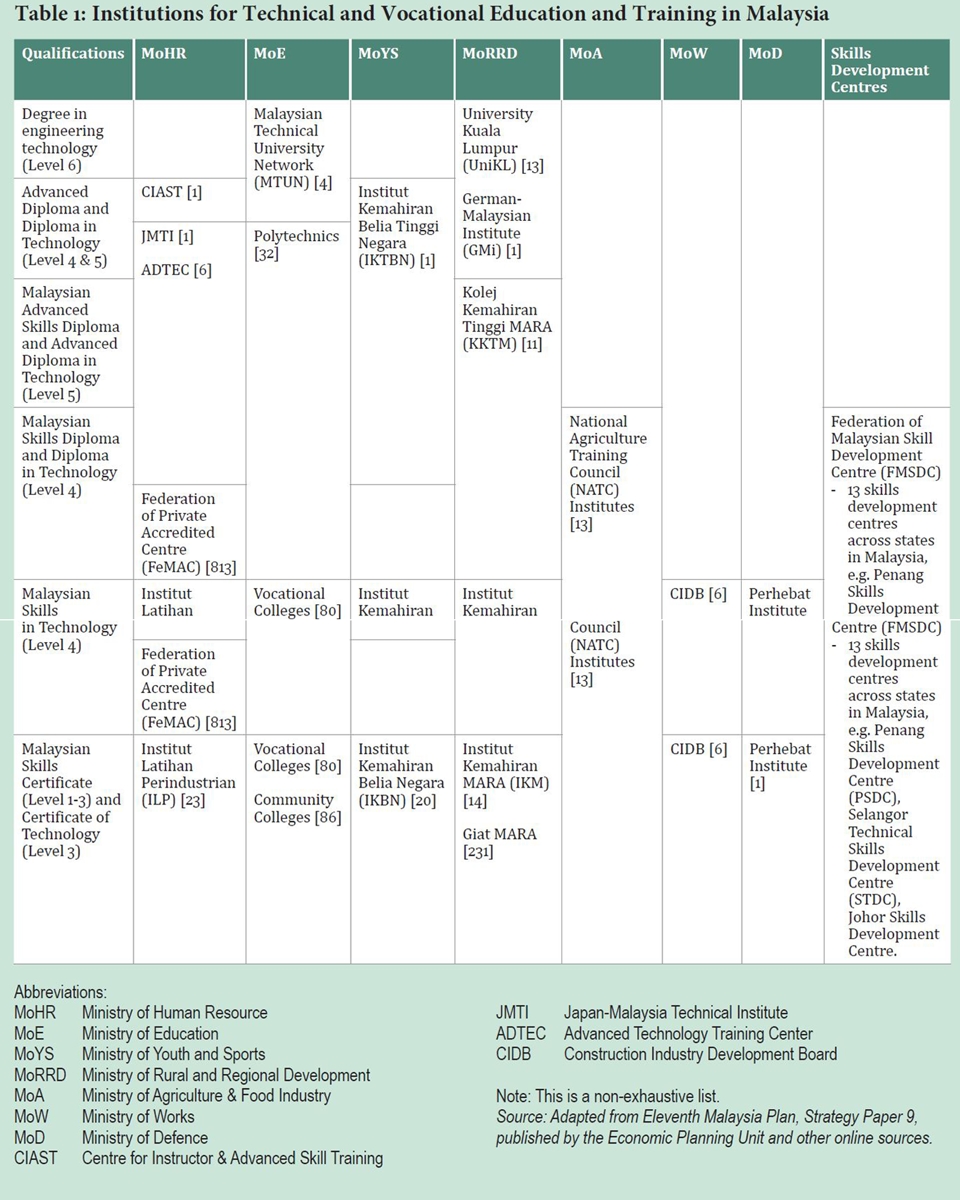

Since then, TVET institutions have mushroomed across states in Malaysia; it was easily recognised as necessary for socio-economic development and for meeting industry needs for skilled workers. More than 1,000 public and private institutions now undertake various TVET programmes, run by seven ministries offering skills certificates, diplomas and bachelor’s degrees.

Table 1 shows the TVET landscape in Malaysia. While the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), the Ministry of Works (MoW) and the Ministry of Defence (MoD) govern training institutes that offer courses related to the respective ministries, courses administered by other ministries are often comparable in essence. For example, the Ministry of Rural and Regional Development (MoRRD), MoHR and Ministry of Education (MoE) offer similar courses for an advanced diploma in technology through multiple TVET outlets, but with different skills accreditations from the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA) – which is under the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) and the Department of Skills Development (DSD) through the National Occupational Skills Standards (NOSS) – which is with the MoHR.

As the country advances industrially, state skills development centres are established across states in Malaysia, with tripartite partnerships offering technical training and skills upgrading to the industrial workforce.

The first state skills centre in the country was pioneered by the Penang Skills Development Centre (PSDC) in 1989. Led by the need to meet industry demand for skilled workers and to close skills gaps, PSDC’s skills enhancement initiatives relied on the participation and support of multinational manufacturers from the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone. This model was later emulated in other parts of Malaysia.

By 1999, all 13 state skills development centres nationwide became part of the Federation of Malaysian Skills Development Centres (FMSDC). This was formed to enhance TVET development by connecting state skills centres with the private sector, academia, and state and federal agencies.

Besides this, Malaysia has more than 800 private institutions registered with DSD under MoHR which are grouped under the Federation of JPK Accredited Centres Malaysia (FeMAC). In Penang, Infogenius Skills Training Centre, Fourier TVET Centre and Infotech Pro Academy are some of the private TVET institutions registered with FeMAC, with their skills courses accredited by DSD.

TVET Employability

On the whole, polytechnics and community colleges administered by MOHE obtained the highest employability rate compared to other private and public higher education institutions in 2021; more than 90% of its graduates were employed within six months of graduating (Table 2).

While individual public TVET institutions governed by other ministries do also demonstrate high employability rates, when grouped together, the level of employability drops, suggesting that some institutions or courses are not doing as well. This situation has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic across the board. For instance, pre-pandemic in 2019, the graduate employability rate for TVET institutions from the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry and the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture only registered between 55% to 65%; it dropped to less than 60% in 2021 (Table 2), prompting the need to revisit the programmes provided by these institutions.

A more valuable insight into TVET employability can be drawn if the data for private TVET institutions is made publicly available.

TVET Initiatives in Malaysia’s Five-Year Plans

The mid-term review of the 11th Malaysia Plan 2016-2020 found improvements in student intake in TVET programmes as well as the development of a more harmonised accreditation system along with the revision of the Malaysian Qualifications Framework. However, the review also found that the TVET landscape is still fragmented, where different TVET institutions and ministries offer overlapping courses, leading to resource wastage and making tracking student intake and output difficult, affecting effective measurement of TVET’s success.

In fact, these issues were already identified in the 10th Malaysia Plan 2011-2015. Other challenges raised include uncoordinated governance, lack of recognition for technologists, fragmented TVET delivery (i.e. no specialisation in public TVET and absence of performance-based rating) and competency gaps among instructors.

To overcome the lack of recognition for technologists, the Malaysian Board of Technologists (MBOT), equivalent to the Board of Engineers, has been established as an apex body for recognising the professionalism of these TVET practitioners. The board also oversees issues such as career enhancement and wage structure.

The 12th Malaysia Plan 2021-2025, again, emphasises the need to improve TVET programmes by enhancing the ecosystem and increasing TVET delivery quality through accreditation, professional and international recognition, and a ranking system.

Moving Forward

TVET is recognised as a significant driving force for sustainable socio-economic development. Rectifying the failings of the current TVET system will be a long process, and is a continuing effort that should be bolstered by progressive policies that streamline TVET national qualifications. Enhancing TVET delivery and rebranding TVET education are processes that are needed if we are to attain an industry-ready talent pipeline.

Footnote:

[1] Ramlee, Mustapha (2022, Dec 1). TVET needs to embrace metaverse technology. New Straits Times. Retrieved from https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/columnists/2022/12/856476/tvet-needs-embrace-metaverse-technology

Ong Wooi Leng

heads the Socioeconomics and Statistics Programme at Penang Institute. Her work lies in labour market analysis and socio-economic development.