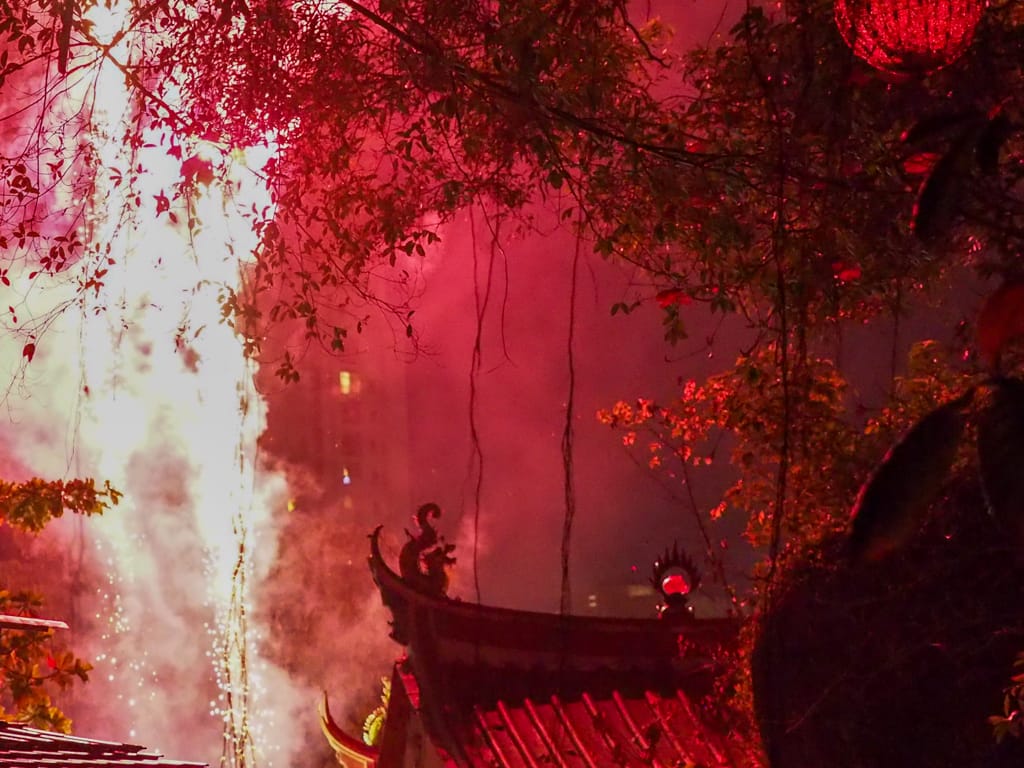

Flames of Fortune: The Chneah Hoay Ceremony at Penang’s Oldest Chinese Temple

By Eugene Quah

May 2024 PHOTO ESSAY

ON THE EVENING of 23 February, my friend—a heritage enthusiast from Penang Heritage Trust (PHT), Ganesh Kolandaveloo—and I went to see the venerable Chneah Hoay (Fire Invitation) ceremony at Hai Choo Su Tua Pek Kong Temple at Tanjung Tokong, held on the eve of Chap Goh Meh, which is the last day of the Chinese Lunar New Year. Since the early 20th century, the ceremony has been used by the Chinese in Penang to predict economic prospects for the new year.

This Tua Pek Kong temple is the oldest Chinese temple in Penang, having existed in one form or another since 1799. It is dedicated to the spirit of Chang Li, a Hakka scholar and political refugee who fled Chaozhou during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor and settled in Penang. Upon his death, he was worshipped as the Tua Pek Kong deity by the overseas Chinese.

Hai Choo Su (Sea Pearl Islet) was the Hokkien name for the nearby islet of Pulau Tikus (see Penang Monthly, May 2022 issue), just northeast of the temple. The Chinese also called it Pek Su, or White Islet, probably due to the distinctive light colours of its boulders, which probably led to the pearl moniker. The grand Thai Pak Koong (Ng Suk) Temple at King Street is a branch of the Sea Pearl Islet Temple.

Each year, the Poh Hock Seah (Precious Prosperity Society)—formed in the 1890s—organises a procession to bring a sacred incense urn from their temple at Armenian Street to the Sea Pearl Temple at Tanjung Tokong. This fire invitation ceremony has been observed for over a century, from around the time of the formation of the society. However, there are reports of a Tua Pek Kong procession from George Town to Tanjung Tokong as early as 1857.

Ganesh and I took many photos of the village and the ongoing festivities. As midnight approached, and the tide reached its highest, the lights of the temple were extinguished, and the gates closed. The temple committee members, who had been patiently waiting for this very moment, gathered around the huge incense urn. They fanned it and observed the height of the resulting flames. This process was repeated three times. The height of the flames indicated the economic prospects for each of the three periods of the new year.

This year’s economy is predicted to range from average to good.

Eugene Quah

is an independent researcher and writer who is working on a book tentatively called “Illustrated Guide to the North Coast of Penang”. He rediscovered the joys of writing after moving back to Penang from abroad.