Hassan Muthalib: A Life Lived in Drawings, Animations and Love of Visual Language

By Rachel Yeoh

May 2024 PENANG PROFILE

HE IS THE Father of Malaysian Animation, a title bestowed on him by former Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak. He was also a recipient of the 2018 Merdeka Award under the category of Education and Community. Earlier in his career, he had won the Best Idea Award by Anugerah Sri Angkasa in 1981 and Best Documentary by the Asia-Pacific Film Fest in 1987.

Hassan Abdul Muthalib had no prior education about film, and animation then was nascent, often appearing as part of the titling in documentaries or commercial work. However, Pak Hassan (as he is called) was able to create long-form animation and caught eyeballs, giving the government reason to invest in this field, thus paving the way for locally-made animation films we see today. Penang Monthly was privileged to sit down with him to chat about his journey.

Rachel Yeoh: Can you briefly tell me how you entered the film industry and what inspired you to keep creating while in Filem Negara and even after you left?

Hassan Muthalib: I came to KL in 1964, and I was working in the Robinsons department store after failing my Form Five. In 1967, I decided to retake my exam. Surprisingly, I passed with a distinction in English and a so-so pass in art. I managed to scrape through, is all I can say.

At that time, I applied to work as a graphic artist at Filem Negara, but I didn’t know what the job was about. 10 people came, and I was the only one chosen. 25 years later, I met one of those who interviewed me, the Deputy Director. I asked him, “Mr. Wong, why did you choose me even though the others had better qualifications and their artwork was much better?” He said I had three things that they didn't have. “(1) Distinction in English, which we had never heard of; (2) You were doing a job that we had never heard of—window display; (3) You taught yourself and you did not wait to be sent for training—that was the kind of people we were looking for.

I was a graphic artist going through titling manually, learning everything on the job. In 1972, I was asked by the new Director General, John Nettleton, to animate a 30-second to one-minute festive trailer. It was for Christmas in 1972. I had never animated before!

My storyboard had the star twinkling, and the three kings were on the camels heading toward the star in Bethlehem, where Christ was born. It was only 20 years later that I realised—when I did the star twinkling—you know, in film visual language, if you have stars in a film, it means your story has something to do with destiny. For me, my destiny was to be in animation.

Today, the Sang Kancil dan Monyet, which I made in 1984, is being re-shown on Facebook again and again and getting positive feedback.

Only later, in learning the language of cinema did I realise that I had been doing things instinctively, the way P. Ramlee’s films affected people. He was using film language instinctively, and today, if you analyse his films academically, you will find that he really did understand—and this is actually coming from what the Malays call firasat, meaning something like intuition; but it’s more than that. For instance, there are three scenes at the beginning, middle and the end of The Lion King, where there are stars in the sky. This means that Simba's destiny is to be the next Lion King, and you cannot run away from that. So, in a sense, I was continuously guided from the very beginning.

These are the things that I've been teaching all this while and I'm the only one in Malaysia teaching this. It is a very basic aspect of cinema that you have to understand in order to communicate with audiences on a subconscious level. Without any words, they can grasp meaning. This is also noted in film theory.

Now, my Sang Kancil dan Monyet was the second short animation film that has been done in Malaysia. The first one was quite long, 13 minutes, done by one of my colleagues, a set designer, Anandam Xavier, during his free time. He began in 1961 and finally completed Hikayat Sang Kancil in 1978.

Now, I was quite lucky because in 1983, when a new Information Minister came in with a new Director General for Filem Negara, he happened to see this film and said, “Oh, this is good!”—even though it was not that good. He called and said, “Why is it not screened?” Of course, there's a political element to it. When the animation was completed in 1978, there was a corruption case involving a Menteri Besar—there is a scene in the film where an old mat that had been thrown away, speaks to Sang Kancil and the crocodile that had caught hold of the leg of the buffalo. He says, “When we are useful, they use us, and when we are not useful, they discard us”. The Home Minister then thought that it reflected on that case, so it was shelved.

By 1983, that issue was over and the film was screened on Hari Raya day. Mine was screened the following Hari Raya, which was a huge success because it was short and used humorous elements in animation, whereas the first one was a direct translation from the story without humour.

In 1974, we were actually already doing public service animations. One that was hugely popular was one where I had Aedes mosquitoes talking to the audience, indirectly getting across the message about the do's and don'ts. I took the comedic approach on serious issues.

Then, I did a live-action public service advertisement on the dadah issue—the first time I directed actors. I was hooked and wanted to be a film director. In 1987 I was given the opportunity to direct documentaries. My first documentary won an award in Jakarta, and I did two or three more.

Sang Kancil dan Monyet and Sang Kancil dan Buaya came out in 1987. I was doing the managing and the administration as well, I couldn't actually sit down and do the animation. I had to plan everything. At the same time, I was also lecturing at the Training Institute at the Ministry of Information. And within it, there was AIBD, the Asia Pacific Institute for Broadcasting Development, and I had to go to India twice under a UNESCO five-year educational training programme. In one month, we made four animation films in New Delhi.

Many years later, I went to teach in Sudan TV, and we made a four-minute short animation film, which had never been done before. They brought in people from BBC and Australia. Nothing happened. But when I came, within four weeks, we made a short animation. So they called me again for the second year, this time to teach documentary film.

RY: You are the “Father of Malaysian Animation”, and though you have not been hands-on for a while, what is the most drastic difference between then and now?

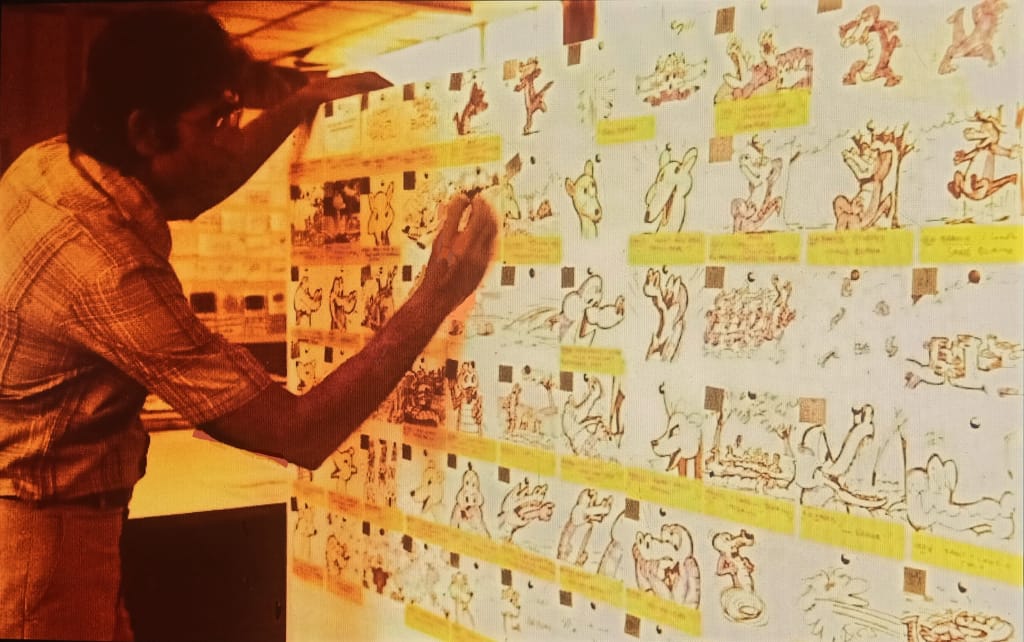

HM: Ah, very big difference! Now everything is done on the computer. You don’t even have to draw anything on paper. When we started, it was all manual. Then, in 1983, when the minister asked to make short animation firms, new computers for animators were released. It was called the QAR - Quick Action Recorder. It was a video thing that checks your drawings—you scan them—and it can playback within five minutes, so you know whether your animation is correct or not.

Before that, you put it under an animation camera, process the film, print the film, you screen it and only after two or three days could you see if it was right or not. If not, you had to redo the whole thing.

Software that could actually help with animation came out in 1988. I was the first animator in Malaysia to be trained in this 2D and 3D software.

In 1989, I was asked to do a commercial for Parkson Grand and Parkson Ria using the characters of Woody Woodpecker, Wile E. Coyote and the Roadrunner. We tested out the software and I was amazed that it could save you a lot of time, especially when it came to mouth movements, as these were different for English and Malay versions of the commercial.

When I did Malaysia’s first animated feature film, Silat Lagenda, with another studio in 1995 after opting out of the government service at age 49, I was the only one who had any experience working on film. We bought a system called US Animation. This was another high-end, incredible machine—you can do visual effects, it can help you to composite, put the characters and the background together, enhance the background—all kinds of things. Animation then still had to be hand-drawn, and because we did not have enough animators, we had to go to Indonesia and the Philippines to work on it.

Now, we have Adobe After Effects that can do some incredible things. What we can do now, we could only imagine in those days. Today, those who are not talented in art but work using the software and understand its capabilities can become animators.

To me, they are not real animators, because you have to learn how to draw by hand first. There are things that you can do that the software cannot do. The animation is not in the drawing. It is the apparent movement between two images—an illusion of movement. The gap is what actually creates the movement in the mind. The retina retains the image for a fraction of a second. It does not disappear instantly. So that's what creates animation.

In 3D, we don’t have that. That's why everything is very smooth. Why is it that Disney Pixar and the Japanese can do something that looks like it's hand-drawn? This is because they have learned how to do it manually. So, they apply it by using the software.

RY: Which animation projects have you been involved in that stand out as the most memorable for you and why?

HM: I haven’t thought about it. When I look back and do a little bit of analysis, I can see that Sang Kancil dan Monyet made me famous. Until today, whenever I meet people, they can mouth the dialogue. This is very satisfying when people remember what you have done. This is after 38 years, almost 40 years!

I was told that during the time, school-children could remember the dialogue, not only from Sang Kancil dan Monyet but also from the public service advertisements.

RY: You mention people mouthing dialogues, were you the scriptwriter for those advertisements and shows?

HM: All the scripts were written by me.

RY: There must be something about how you string the sentences in your script then, that makes them memorable.

HM: I wasn’t specifically thinking about what kind of dialogue I should write. But just a little about my background… when I was in primary school, Westlands School in 1955, there was an English teacher who would always tell stories. I became interested in reading comics—I was reading classics illustrated. I read one book a day.

In secondary school, I joined the USIS library, the United States Information Service Library on Beach Street. You know the building called India House?

RY: Yes.

HM: The library was on the ground floor. From British fiction, I moved to American fiction and was enthralled by the adventure stories. I walked from Jelutong to Beach Street because I could not afford the five sen bus fare. I came from a really, really poor family.

I was also reading nonfiction, astronomy, geology, biology… the books had so many wonderful illustrations and photographs. The visuals made me want to read the text.

Can you imagine how reading must have affected me?

I failed my Form Five because I never read school books—only storybooks! But of course, I got a distinction in English—the only one in my school. The headmaster called me and said, “Hassan, you're a joke! How can you get a distinction in English and fail all the other subjects when it should be the other way around?”

I was also studying civilisations. So once you know about other civilisations, you will begin to appreciate your own and that diversity actually helps you—this is what Mark Twain said, “Prejudice and bigotry are the enemies of travel”—these are the things that you learn in anthropology. And writers need to have this knowledge.

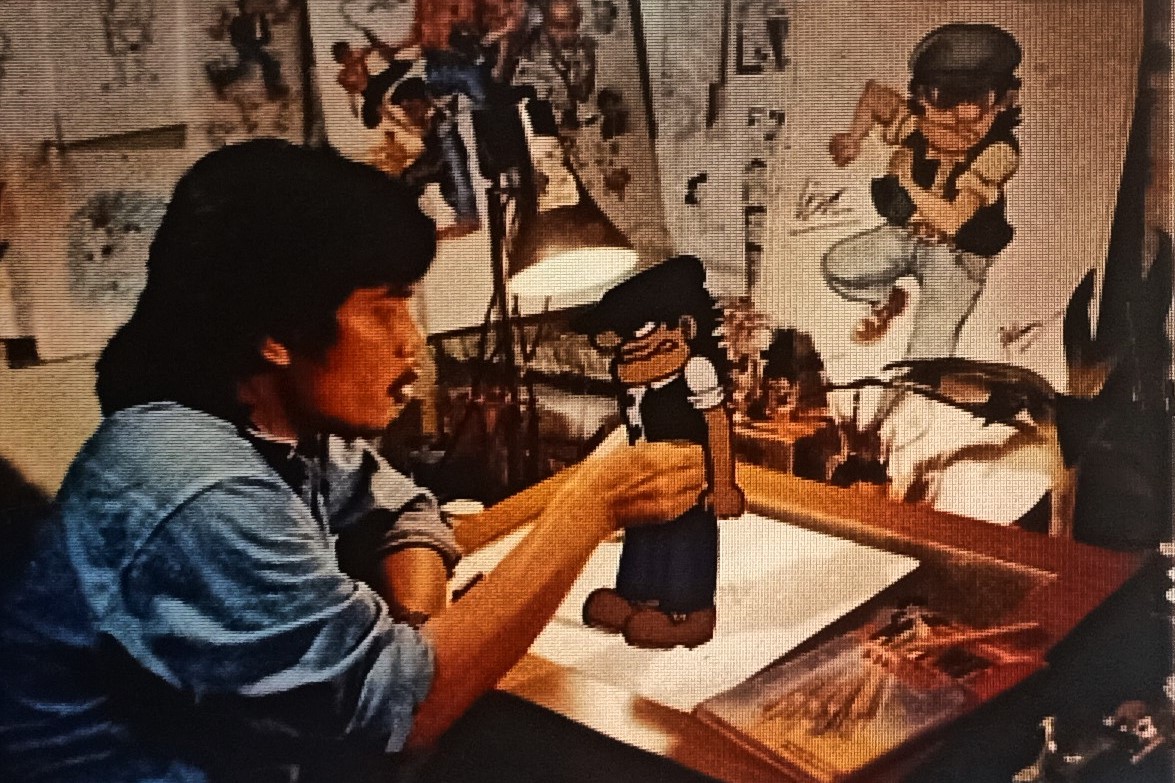

The other thing was drawing. I was not born with talent, but I loved art so much that I copied it and suddenly, I was an artist. The same thing happened when I got into animation. I was copying the animation from other Disney films I borrowed from RTM (Radio Televisyen Malaysia). I used a magnifying glass to look at a 16mm film and copied the walking effects, birds flying and so on.

I was training myself—copying the artwork of famous painters and animation of famous filmmakers. Now, if you’re copying the masters, how can you go wrong?

RY: How accessible are resources, training and funding for aspiring animators in Malaysia? You had to learn on the job. But after all these years, do you think that access to technology for budding animators has improved?

HM: Our biggest drawback is the market. If we are just animating for our audience, we have to keep costs very, very low. But animation has a long shelf life, which means after a certain number of years, it can be reshown or sold to other countries. Suppose you have cooperation among ASEAN countries or with other Asian countries, we could actually create a market for all these countries because they need content for their TV station.

And I always say that we cannot train animators now. Because the software and technology has made it so easy for almost anyone to be an animator. Therefore, the next level is to create animation filmmakers. Even if you don’t become a creator, you will be able to work better with a director because you understand his crowd, you understand directing, writing, acting and so on. It is not about drawings that move but movements that are drawn. Therefore, we are talking about acting, the story, directing, cinematography and editing.

If you look at the syllabus of European countries or Disney Studios or the Sheridan College in Canada, they teach students to be animation filmmakers, not animators—and they will become the best in the world. This calls for a totally different kind of thinking.

We now have to focus on training our trainers—they are the “frontliners”.

RY: Then what do you think are the key challenges faced by the Malaysian film industry in terms of production, distribution and promotion?

HM: I am happy to see that Upin and Ipin, BoBoiBoy and Ejen Ali have already made it internationally. They have a large staff; I cannot imagine the overheads every month. If you're making a feature film, it will take two to three years. Imagine how much you're paying them a month. Let's say, at a minimum, you're paying RM200,000, and in 10 months, it is RM2mil. Even if you made RM30mil at the box office, you still have not made a profit yet.

I know the producer of Upin and Ipin, Haji Burhanuddin. He is a very astute businessman. His team is very good at what they do. But there is a lack on the story aspect, especially in getting across the story visually. This is where understanding visual language is very important. If you want to go global with animation, these are the elements that are needed.

There is storytelling and there is story-making. Storytelling is the story of characters and so on. Story-making is the technique of putting that story onto the screen. And it cannot be done only through dialogue. You have to use visuals to support them. And this is what is very much lacking in all our films. I can say that, for me, Ejen Ali is so far the best when it pertains to the story. And if you notice, Ejen Ali’s eyes are very detailed. You may not notice this, but your subconscious mind picks it up, which is why he appears more lifelike compared to other characters.

RY: How do you think the socio-political climate of Malaysia has influenced the industry?

HM: Actually, I can say that the animation industry flourished because of government support. In 1983, when Mahathir Mohamed became the Prime Minister, one of the first things he said was, “We want to reduce the number of television clips on our TV.” I remember there were 35 TV series at the time; not a single one was local. So in 1983, the Information Minister came and he said, “We have to have our own TV series. So go ahead and make 13 episodes of Sang Kancil.” At that time, I had just been promoted to be the head, so I could not say, “Sorry sir, we don’t know how to do that.” So I just crossed my fingers and said, “No problem”. But then you see, if I had not accepted it, I'm sure our industry would have taken very, very long to develop. But when things moved, other people got inspired by what I had done.

Mahathir got things moving at the very beginning, and by 1994, I was asked by the Ministry of Information to present a paper to the Parliamentary Secretary about animation and how to get our own TV series. He thought it was just getting a cartoonist to do animation. I said, “No way!”

I presented my paper, then he began to realise that it was not going to be easy. But at that time, they were already thinking of creating our own series and going to the Ministry of Finance to get a special grant to pay for local episodes. I was on a panel together with other people to look at two pilot episodes; one was Sang Wira and another was Usop Sontorian.

They then asked, “How much should we pay for a half-hour episode?” I said RM60,000 and they nearly fainted! They said that the Ministry of Finance will never approve. So they asked “Why don't we give just RM45,000 and as it improves, we can increase?” So that's how the TV series started in 1995 with Usop Sontorian.

They wouldn’t give more than RM45,000 because buying shows from Disney or Warner Brothers only cost USD500 per episode. They could charge very low because they were on the world circuit.

This is why I say that if you have a deal with either ASEAN countries or Asian countries, then our shows could go from country to country. But there must be a unit specifically looking into this. And we will generate jobs for all the animators, the directors, the writers, and so on. Right now, we don’t really have a proper industry. We just have different people doing different things. There has got to be some political will.

For Upin and Ipin, there just happened to be two characters in a feature film, and the studio decided to take the two characters to make short episodes for TV—it became a huge hit; in Singapore, in Brunei and Indonesia, especially.

So all that money that was spent by the Multimedia Development Corporation (MDeC) in the 90s to train animators and provide them with work did help. They also understood about marketing overseas and distribution. They brought in people from overseas to advise. So actually, we are making a lot of money every year; I think two years ago, the biggest box office hits were animations.

RY: That's so encouraging to hear. Let's talk about multiculturalism and film. How do you think animation films can be used to help the country achieve the unity that Malaysia covets?

HM: The Ministry of National Unity should work with the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture to develop a special budget for how to unite the nation through animation films.

Since Upin and Ipin has crossed boundaries, together with BoBoiBoy and Ejen Ali, they should make use of this but also create new characters from our folktales, from our legends and our literature. I've spoken about this to some relevant people, but I don't see anything happening. We need a separate department. And yes, it should be government-funded at the beginning, then they should go on their own, and look at the commercial aspect of it.

Writers also need to be trained because not everyone knows how to write for animation—that is totally different from writing for live-action films. It's not about fast-moving, fast-cutting and so on, which is more like any video game. They need to know how to tell stories cinematically—they need a deep understanding of cinematography, editing, the use of sound and, of course, mise-en-scène—how the director arranges everything within the frame—all this has meaning. For example, if a character stands on the left during a fight, he will lose; if on the right, he will win. This is visual language. If you put a person in the centre, you're breaking the rule. Our animation filmmakers have to understand visual language.

RY: What are your hopes for the animation industry?

HM: I truly cannot see where we are headed. I think they should study the European approach to animation. But ultimately, they need to have a strong foundation in filmmaking—understanding editing and so on. Otherwise, when they do a storyboard, they are just imagining it—they don’t know the actual rules. Film dynamics is a very important area but it is not being taught in Malaysia.

I can say that the funds given to the animation film producers have been properly utilised, and you can see that on the screen. That is the good thing about it. So I hope they will increase the budget for animation feature films and help it rise to the next level.

RY: Thank you so much for your time, Encik Hassan.

HM: Alright!

Rachel Yeoh

is a former journalist who traded her on-the-go job for a life behind the desk. For the sake of work-life balance, she participates in Penang's performing arts scene after hours.