The Present

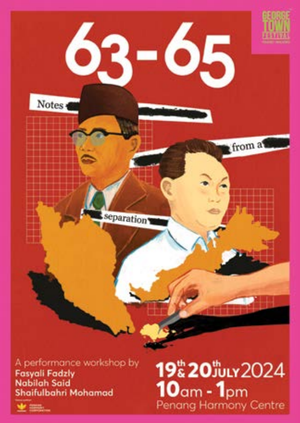

AN ALTERNATIVE PRESENT haunts Boo Junfeng’s “Happy and Free”, a speculative karaoke video commemorating “a Malaysian Singapore that never came to be”, which “provoked […] a deep sense of unease, loss, longing and finally, melancholy”. Played on screen at the Penang Harmony Centre as part of the 63-65: Notes From a Separation performance workshop, Boo’s uncanny vision of a united Malaysia and Singapore was showcased alongside an artificially recreated speech by Tunku Abdul Rahman, prepared specifically for the audience. Resurrected through voice cloning technology, a digitised Tunku reads the proclamation of Singapore’s separation in Parliament. But it is still too polished and seamless, and his unrecorded emotions remain elusive.