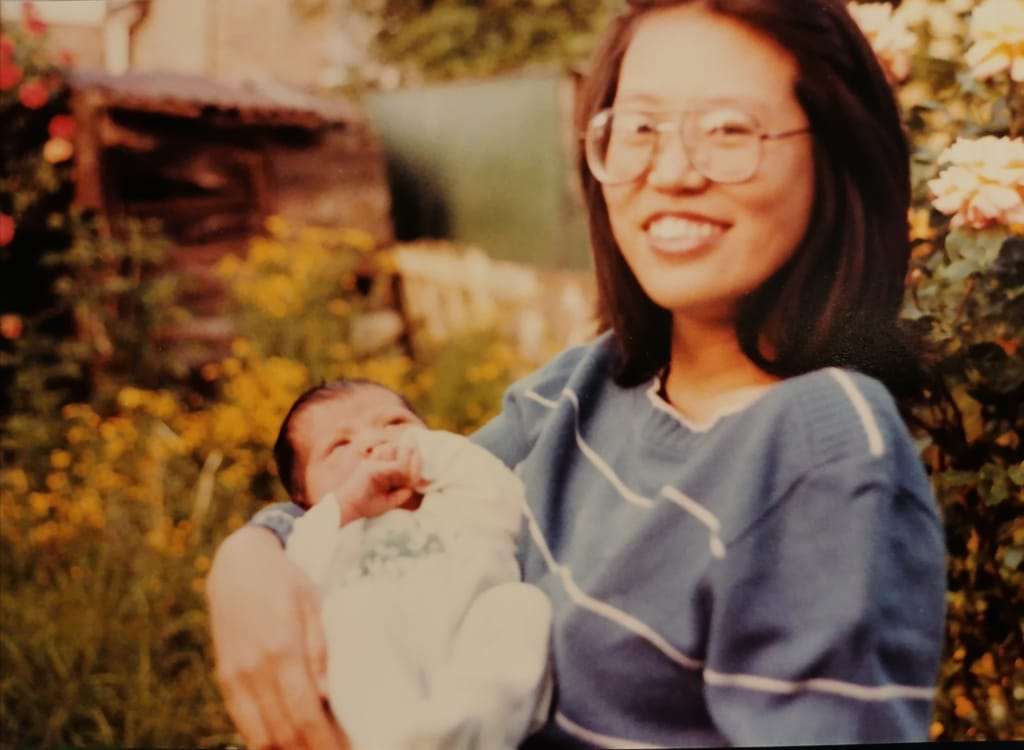

Left in Limbo: The Struggle for Citizenship for the “Overseas-Born” Is Not Over

by

Emilia Ong

Previous Post

Kopi Jackfruit Monkey—Feeling Life in George Town

3 min read

I HAVE ALWAYS loved two things in life: travel and art. Combining these, my wife and I have travelled the world, stopping in particularly inspiring locations li...

Next Post

Keeping the Curtain Open for Peking Opera

7 min read

GuoGuang Opera Company, formed in 1995, was the outcome of the historical development of jīng jù in Taiwan. Today, it is celebrated for its innovative approach of presenting the stories of traditional opera through a modern lens, alongside creating new scripts for performance.

You might also like

Women! Let’s Rush to the Gym and Embrace Strength Training

5 min read

GROWING UP, I often heard adults in my family complain about their inevitable decline in strength and increasing frailty, resulting in higher dependence on othe...

Write for the Curious Child, Read to the Inquisitive Mind

5 min read

OUR BELIEF SYSTEM is formed by what we are taught and our lived experiences, which then influence our decisions and perceptions. What stands in between with one...

CEO Hari: PSDC Stays on Course on Penang’s Industrial Voyage

10 min read

APPOINTED AT THE start of 2024 as CEO of Penang Skills Development Centre (PSDC), Hari Narayanan has led a long career juggling both academia and industry for a...