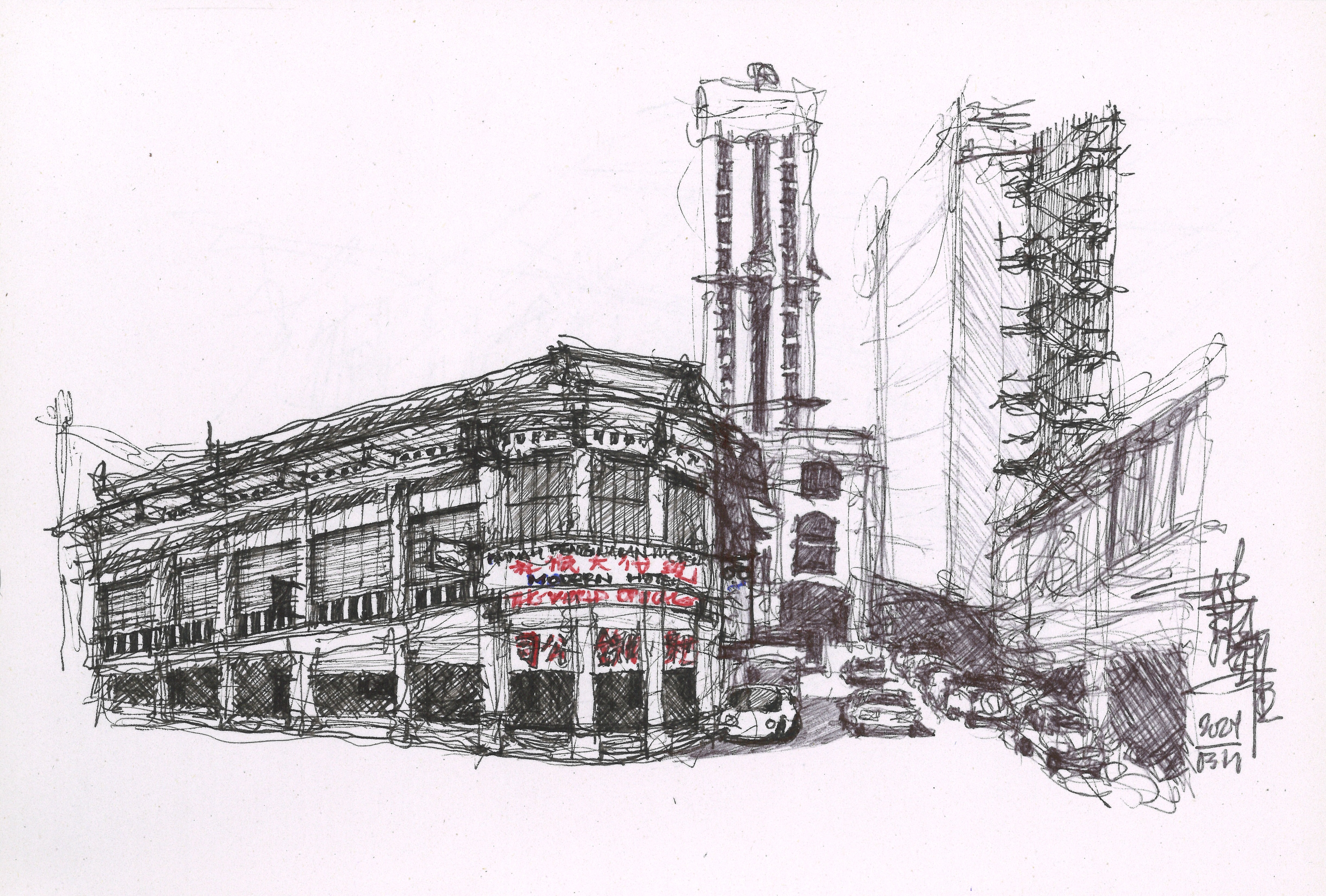

Spaces, Vigour and Funding: Keeping George Town’s History Palpable

by

Laurence Loh

Previous Post

The Significance of the Revival of the Sending-of-the-Royal-Ship Ceremony in Penang

7 min read

SINCE THE INCLUSION of the Sending-of-the-RoyalShip ritual (送王船) in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list on 17 December 2020, this ceremony, which orig...

Next Post

Events in July

3 min read

INCLUSIVITYOrganised by SHANZ Early Intervention & Learning Therapy, the Perfectly Imperfect Charity Campaign is an event aimed at raising awareness abo...

You might also like

Women! Let’s Rush to the Gym and Embrace Strength Training

5 min read

GROWING UP, I often heard adults in my family complain about their inevitable decline in strength and increasing frailty, resulting in higher dependence on othe...

Write for the Curious Child, Read to the Inquisitive Mind

5 min read

OUR BELIEF SYSTEM is formed by what we are taught and our lived experiences, which then influence our decisions and perceptions. What stands in between with one...

CEO Hari: PSDC Stays on Course on Penang’s Industrial Voyage

10 min read

APPOINTED AT THE start of 2024 as CEO of Penang Skills Development Centre (PSDC), Hari Narayanan has led a long career juggling both academia and industry for a...