Fort Cornwallis: A Symbol of Fortitude More than of Conflict (APR 2021)

By Marcus Langdon

COVER STORY

FORT CORNWALLIS IS undoubtedly Penang’s most iconic surviving building from the era of English East India Company (EIC) settlement on the Island. But after 235 years, what is its legacy to Malaysia?

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was progressively gaining a monopoly on trade in the East Indies from their bases in Java, Sumatra, Malacca (Melaka) and the Moluccas Islands (Maluku). The EIC deemed it essential to obtain a strategic toehold in the region, not only to ensure its important trade route from Britain to China was kept open but to secure its significant settlements in India as well.

The circumstances of Penang’s cession to the EIC, and by default the British Crown, are not examined here, but with 16 years of local trade from his base in today’s Phuket, Thailand, Francis Light, along with fellow “country trader” James Scott, were key players in urging and facilitating the settlement.

The Building of the Fort

On July 17, 1786, Light’s ill-equipped landing party of a few Europeans and 135 poorly trained men from the EIC’s Bengal forces set foot on Point Penaga and immediately got to work clearing an adequate area on which to set up camp. With just six cannons, and being “hourly in dread of some mischance, from the ignorance of the people with me, and the envy of our neighbours”,1 personal protection was a priority.

Within two weeks of landing, Light had enough land cleared to commence building a fort. The tall, straight trunks of the abundant nibong palm (Oncosperma tigillarium) were utilised by placing them in the ground vertically to create an enclosed square of 500ft x 500ft, comprising two parallel walls seven feet apart at the bottom, but touching at the top and infilled with logs and sand.

It was not until the following year that this hastily built enclosure was given the name Fort Cornwallis, after Light sought permission from the new Governor General of India, Charles Cornwallis.2

Light alluded to threats arising from the jealousy of others as a prime reason for the fort’s construction. By creating a settlement and port where local traders could do business under British protection without the fear of being heavily taxed, he risked raising the ire of regional sultans whose income was partly derived from such taxes; from the Dutch at Malacca and even from the Siamese, who considered Kedah a vassal state but were not engaged in the talks to cede Penang to the EIC.

Perhaps most feared were the innumerable pirates that patrolled the Strait in heavily armed perahus but no such threat arose until 1791. This had much to do with Light’s reputation. He was respected by the Malays, understood the region’s politics, and knew all the sultans from his years of doing business with them.

It is true, however, that despite Light’s regular pleading, the EIC and its overlord, the British government, were unwilling to ratify the original terms of cession of Penang. In early 1791 this led the Sultan of Kedah to gather an estimated force of 10,000 men and 250 armed vessels, drawn from far and wide, to evict the EIC from Penang. In April Light sent soldiers and marines on a predawn raid to pre-empt imminent attack.

Fearing the worst, many inhabitants had left the Island by then, burning their houses and crops behind them. To live and trade on an island under the protection of the British was seen by its inhabitants as the key to the success of Penang, and this instance is a great example of what Fort Cornwallis represented to them – security and safety. While this prevailed, all was fine; but when threatened, confidence rapidly waned. The action resulted in the signing of a revised treaty which, along with cession of a strip of coastal land (Province Wellesley) in 1800, resulted in an accepted peace.

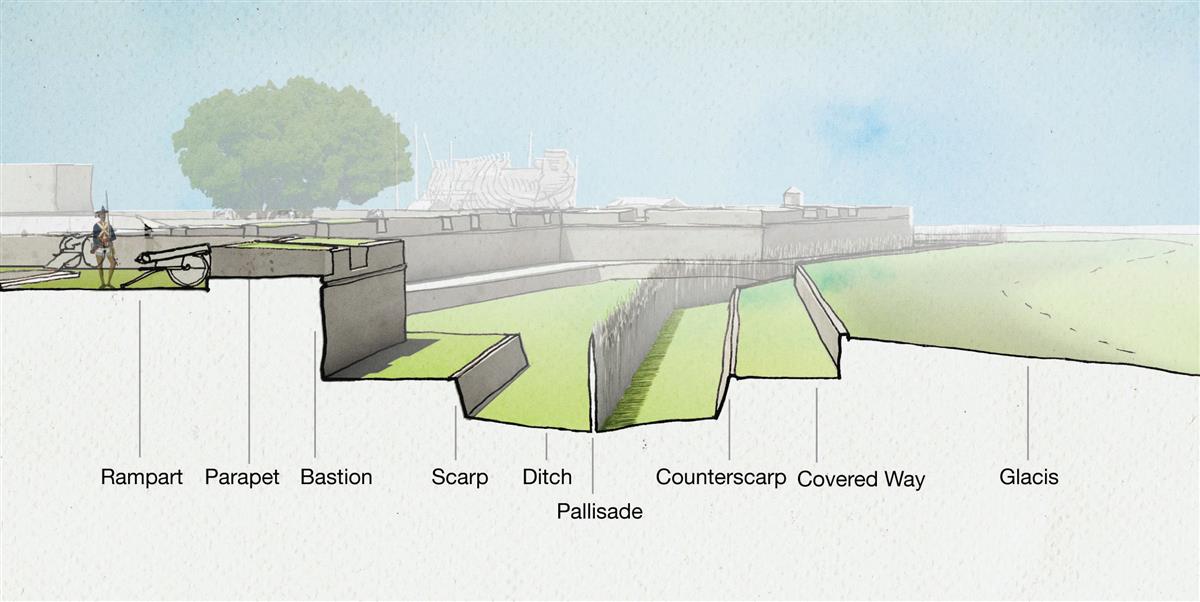

Two years later, an unexpected threat to the settlement came from the other side of the world. France and Britain had declared war upon each other. This probably meant little to local traders but to Light, an ex-British naval seaman, it was significant. Without waiting for permission from his superiors in Bengal, he immediately began replacing the rotting timber fort with a solid brick structure. Built to a standard military “star” design, though on the same footprint and to the same dimensions as the timber fort, the walls were completed in 1794 to rampart level just weeks before Light’s death on October 21 the same year. These original walls partly remain today.

Reinforcing Structures

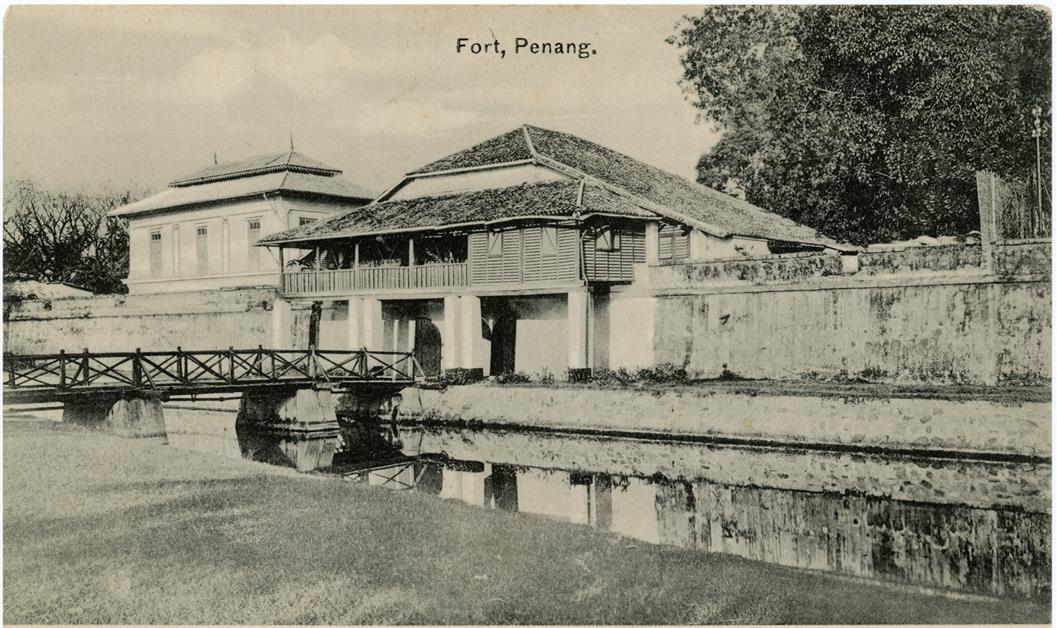

With the rise of Napoleon and the re-commencement of war between France and Britain in 1803, Fort Cornwallis’ defences were further strengthened under Lieutenant Governor Robert Townsend Farquhar. Brick parapets were added; the moat (previously a dry ditch) was constructed, along with defensive outworks beyond the moat facing seaward and a glacis on the landward sides.

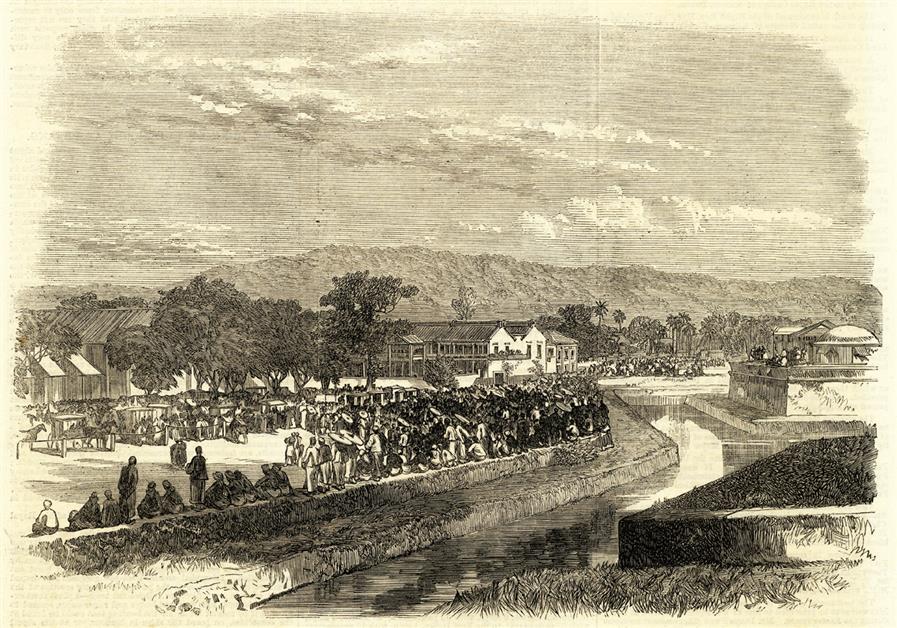

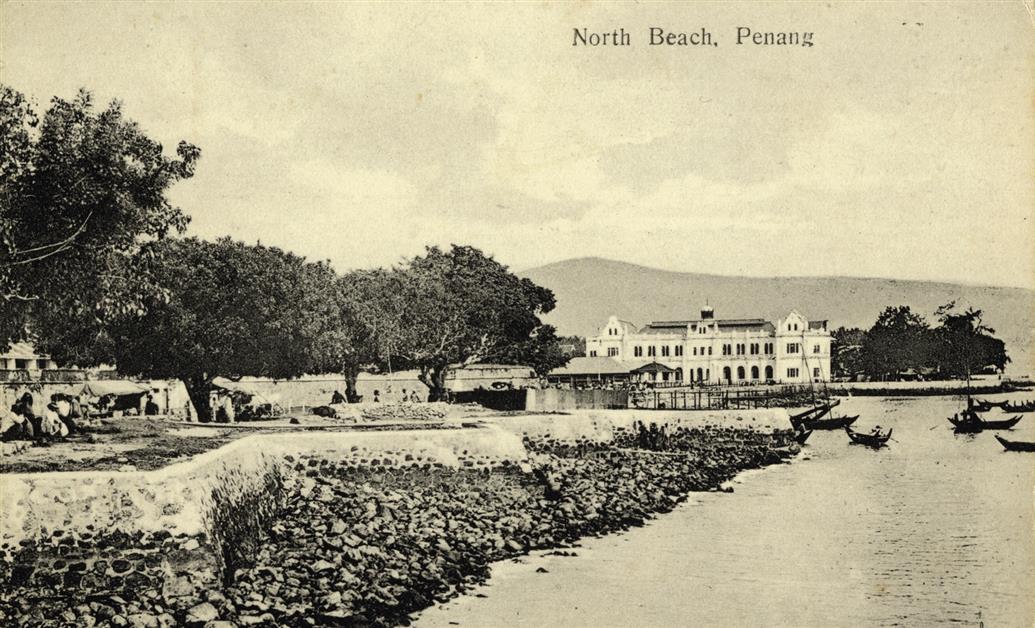

The small, winding Prangin River was converted to a wide canal following today’s Jalan Dr. Lim Chwee Leong and Jalan Transfer to surround and isolate the Point. A drawbridge crossed the canal on Jalan Penang. Cannon emplacements were spread around the circumference, including a large semi-circular battery mounting eight heavy cannons at the end of today’s Jalan Green Hall. Despite such works, the town was deemed by visiting military personnel to be relatively defenceless, the fort being too small, too light in construction, and easily overcome by cannon fire from ships at close range.

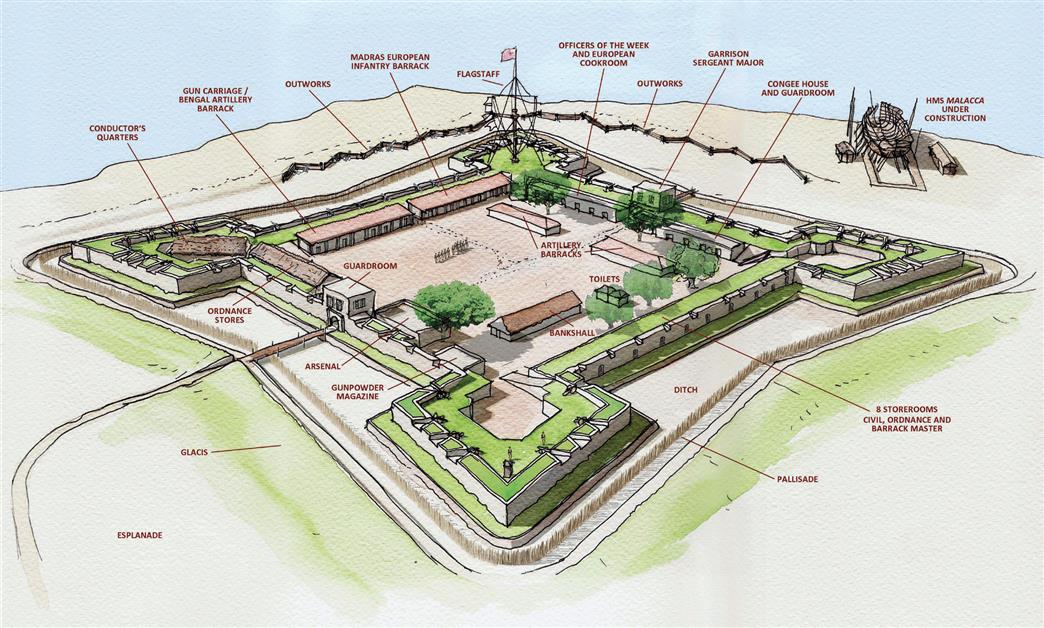

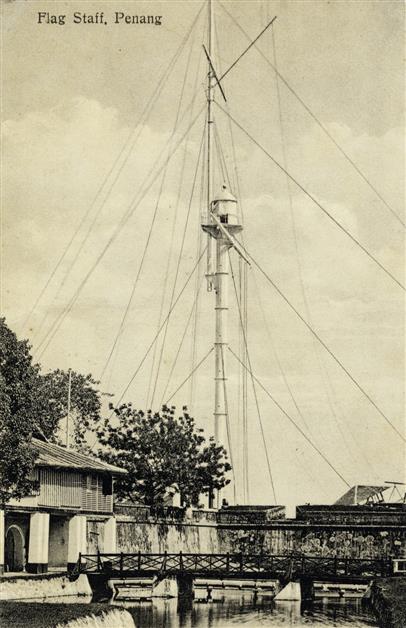

Inside the fort were barracks to house small contingents of army personnel. These were mostly “golundauze”, Bengal Artillery troops who were specially trained to operate the heavy guns. There were guardrooms and officers’ quarters over the eastern and western gateways, with rows of barracks, storage rooms, kitchens, gunpowder rooms, toilets etc. around the inside of the walls. A tall, timber flagstaff on the fort’s northeast bastion was used to communicate with manned flagstaffs on Mt Erskine and at Bel Retiro on Penang Hill.

Using semaphore, the number, size, type and nationality of vessels approaching the Island could be determined, giving the fort time to prepare, either for hostilities or to welcome important visitors. A common misunderstanding is that the EIC’s Penang administration operated from the fort. Although Light initially lived inside the timber fort, as soon as was able, buildings were constructed elsewhere and the fort became strictly a military compound until the 1880s.

Other artillery troops, sepoys and marine “lascars” were housed in rows of attap huts known as “lines” which were, over time, located at the top end of Lebuh Chulia, on Jalan Penang and later, on extensive areas of land around today’s Polo Ground and Jalan Western. Contingents were also sent from the Bombay (Mumbai) EIC army and navy, and the Madras (Chennai) army. They were often paraded on the Esplanade adjoining the fort. The Esplanade is a military term for an open space that forms an integral part around a fort; today, this is referred to as Padang Kota Lama.

Towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars, a maritime war broke out between Britain and the US. There was great concern that an attack would be launched since many an American vessel had called at Penang and knew the weaknesses of the Island’s defences. In 1814 the earlier seafront outworks were massively upgraded to mount a battery of 32-pound cannons (i.e. they fired a 32-pound cannonball), and a purpose-built storage room to hold 650 barrels of gunpowder was constructed in the southwest bastion.

A popular “urban myth” is that this building, with its arched ceiling and steeply-pitched “bombproof ” roof, was a chapel, but it was never used as such. The old barrack against the inside of the northern curtain (wall) was replaced with a new two-storey building to house additional personnel.

Such works meant that when global peace came in 1815, the fort was at its peak preparedness. A report of July 1814 listed 76 cannons and one mortar mounted on the fort, though it was designed to mount 110 cannons and 12 mortars. Years passed and many armaments were withdrawn to storage to protect them from the harsh sun and rain. In fact, Fort Cornwallis never had cause to fire anything but blank shot, regulated numbers of which were used to salute officials of higher rank – both civil and military – on their arrival and departure from the Island; to mark the start and end of the military day; the arrival of the mail; royal occasions such as birthdays; deaths of notable persons; and warnings: three shots meant fire had been spotted in town. The fort therefore also functioned to keep the residents of Penang informed of daily occurrences.

The Fall of the English East India Company

The year 1830 signalled the end of Penang’s glory days as the fourth Presidency of India; a status it had enjoyed for 25 years. The economy suffered as the highly paid civil service and military presence was heavily reduced and the settlement was downgraded to a Residency under Bengal. This in fact was a precursor to a decline in the EIC’s prominence in global affairs. Four years later, its monopoly of trade between Britain and China was abolished and the Company became administrative only. Although this opened up trade to private firms and individuals, for Fort Cornwallis it meant that as funding was tight, little but basic maintenance was undertaken for the next several decades.

The EIC was abolished in 1858, which began a decade of transition to full colonial rule by the British government in 1867. During the same year, the Penang Riots between the Red Flag and White Flag factions saw women and children huddling within the fort walls for protection – it was perhaps the first time the fort was used for civil purposes. British army regiments occupied Fort Cornwallis until around 1882, when it became a base for the Sikh and European police force. During this time, the substantial building over the eastern sea gate became the official town office of the governor when visiting Penang. When the governor was in residence at the fort, a flag was flown on a specially erected flagstaff and a Sikh guard in full dress uniform was placed on duty. The western gatehouse, which in the 1820s functioned as the Post Office, was utilised by the Sikh troops as the first gurdwara in Penang.

The first lighthouse erected on the fort was of masonry and fabricated metal construction with a fixed red light and became operational on January 1, 1882. Within two years, it was replaced by a combination iron flagstaff and revolving light and relocated to Pulau Remo, where it still stands today. The flagstaff light was in turn replaced by the current 70-foot-high iron structure, which was completed in January 1914. This corner of Fort Cornwallis also functioned as a meteorological station for Penang for over a century.

Demolition Discussions Abound

In 1895 following its decommissioning, rumours of plans to demolish part of the fort surfaced. Although the cannons were moved out the following year, no demolition occurred. Around the turn of the century, it became a base for the Penang Volunteers, and later the Chinese and Malay volunteer regiments. A new building, 150 feet long, was constructed inside the fort to house a drill hall, canteen, dining room and offices, as well as a gymnasium, stables, and other ancillary buildings.

But with the completion of Swettenham Pier in 1904 and the port’s burgeoning entrepot trade in tin, rubber, copra, tapioca, coconut oil, tobacco and other goods, temporary goods storage was at a premium. Eyes were again turned to the defunct fort as potential valuable land for more goods sheds, but procrastination and the first World War diverted attention elsewhere.

By 1920, it had again been resolved to demolish part of the fort to open it to the Esplanade but first, the moat had to be filled in to allow access to machinery. This was completed in 1922 by the Penang Harbour Board under the pretext of controlling malaria. Most of the fort’s internal buildings had been demolished by 1930, as had the western wall, leaving a U-shaped shell open to the Esplanade. Agitation to demolish the fort completely remained until the Straits Settlements Governor, Sir Shenton Thomas, ordered in January 1935 that it be preserved. Without his intervention, Fort Cornwallis would have been lost forever; and with this decision, came renewed interest.

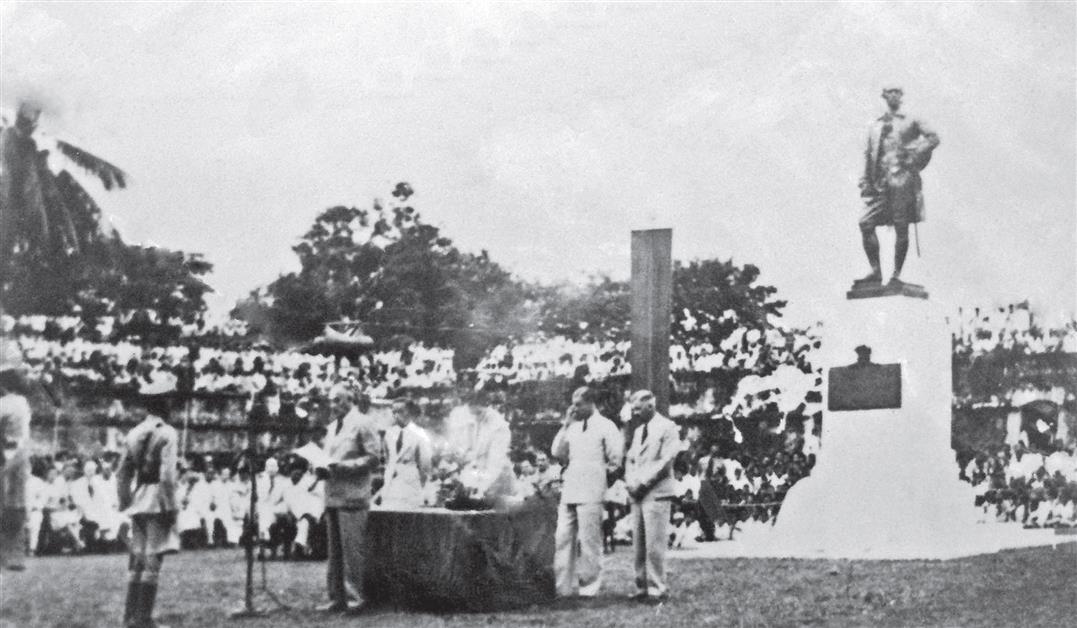

The idea of a memorial to Francis Light gained strength, as did plans to commemorate the 150th anniversary of his raising the British flag in Penang. A re-enactment, suggested by the Malay Company of the Penang and Province Wellesley Volunteer Force, was held at the fort on August 11, 1936.

The launch of a design competition for a suitable memorial eventually led to a bronze statue of Light by Frederick John Wilcoxson. It was commissioned from England at an estimated cost of $9,000, to be mounted on a high granite plinth made in Penang for $2,600 – the money was raised through public contribution. On October 3, 1939 and in front of 1,000 guests, the statue was unveiled at its location on Lebuh Light by Governor Thomas.

The Start of World War II

War had then just broken out in Europe and just over two years later, on December 19, 1941, the Japanese invaded Penang and remained in occupation until their surrender to British forces on September 4, 1945. During this time, the fort and its Esplanade were utilised as a site for military workshops and storehouses serviced by a light railway which ran in a loop from Swettenham Pier, through the fort, around the Esplanade and back to the pier.

Some of the foundations of this railway have recently been unearthed inside the fort. Light’s statue was removed by the Japanese to make way for a huge two-storey administrative building fronting Lebuh Light. After the war, this building was utilised as the George Town Post Office until completion of the Tuanku Syed Putra building and Post Office on Lebuh Downing in 1962, when it was demolished.

The fort was not unscathed by the war. During Allied bombing in early 1945, a bomb fell in the centre of the row of arched storerooms inside the fort, destroying three of them. These were rebuilt in concrete by the Japanese and the delineation is clearly seen today. Despite this, throughout its long history stretching back over two centuries, Fort Cornwallis never fired a shot in anger.

After the second World War, plans were soon underway to restore the fort and the Esplanade, with the Council appealing for any news on the location of old cannons and other artefacts. On February 19, 1952, Fort Cornwallis was declared an ancient monument and in 1977, it was gazetted as a National Monument. The amphitheatre and ancillary buildings seen today were constructed in the early 1970s to encourage public events at the fort.

Between 2000-2001, the fort was extensively restored in a project undertaken by Universiti Sains Malaysia’s (USM) School of Housing, Building and Planning, in conjunction with the Department of Museums and Antiquity. This restoration included reconstruction of the demolished western curtain and gateway, and much-needed stabilisation of the walls.

Today, efforts are being made to restore the fort to its former glory under a tripartite partnership, the George Town Conservation and Development Corporation (GTCDC), between the Penang state government’s Chief Minister Incorporated (CMI); Think City, a subsidiary of Khazanah Nasional Berhad; and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, with the approval of Jabatan Warisan Negara, to manage the project.

Together with the archaeological department at USM, works to date have involved exploratory excavation of the Western and Southern moats and some internal areas. Restoration and conservation experts have restored the 10 arched storerooms inside the fort and plans to open them to the public are afoot.

Though perhaps insignificant as a defensive work, there is no doubt Fort Cornwallis played a crucial role in the successful establishment of one of the world’s most distinctive multicultural centres. The blood, sweat and tears of the multitudes of people from various cultural backgrounds who ventured to the Island seeking a better life are embodied in the very bricks and mortar of this building. For the convicts, labourers, tradesmen, merchants, farmers, shopkeepers, families, and sojourners who flocked to the Island – attracted by British protection in a region of high risk and uncertain reward – it represented opportunity. The benefits they derived built Penang.

This then, may be its enduring legacy in the story of Malaysia. Today, the structure forms an intrinsic part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site listing of George Town, with Melaka, in 2008. In recalling his 1820s childhood in Penang in later life, J.T. Beighton still retained vivid memories of Fort Cornwallis “with its green slopes, its broad ditch, its pierced ramparts, and a few guns with pyramids of shot here and there, and some 60 or 80 soldiers; so tiny as to seem almost a toy, but such power lies in it and all that it represents, that it is far-reaching in its influence as a punishment to evil-doers, and a praise to them that do well.”3

Footnotes:

1 Light to Andrew Ross, 25 September 1786 in Alexander Dalrymple, Oriental Repertory, Vol.2, London: printed by George Briggs, 1795, pp. 583–600.

2 Straits Settlements Factory Records (SSFR), Reel 3, Vol. 2, Fort William Proceedings in Council, 11 April 1787; Light’s letter seeking permission to name it Fort Cornwallis dated 5 March 1787.

3 John Timothy Beighton, Betel-Nut Island; Personal Experiences and Adventures in the Eastern Tropics, London: Religious Tract Society, 1888, pp. 15–16.

Marcus Langdon

is a passionate historian of Penang’s amazing history. He has published several books and is a director of Entrepot Publishing.