The Elaborate Meaning of the Indian Marriage Necklace

By Preveena Balakrishnan

FEATURE

JEWELLERY CAN mean many things, all the more so if placed in their traditional contexts.

In the Indian tradition, the Rig Veda, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas all speak of jewellery owned by members of the royal family, ministers, soldiers and the common men. In the Tamil epic Silappadikaram or The Tale of the Anklet, the young merchant Kovalan was unjustly executed after he was framed by a wicked goldsmith for stealing the queen’s anklet. He was in fact in possession of his wife, Kannagi’s anklet.

In Sundara Kandam, the fifth section of the Ramayana, through the monkey god Hanuman, jewellery pieces were exchanged between Lord Rama and his kidnapped wife, Seetha. Rama’s signet ring was given to Seetha as identification, and to him, Seetha’s pearl hair brooch[1].

Beyond beautifying the human body, jewellery can be storied examples of social constructs, e.g. in identifying one’s economic standing, wealth and more importantly, a woman’s marital status. This holds true on the Indian continent, as well as in the Indian diaspora, including that in Malaysia.

The wedding necklace, Thali, for instance, is worn to symbolise longevity in a marriage. Records of oral history explains its etymology; Thali derives from the words Thallai Olai, Panai Olai and Olai Chuvadi which in English, translates to Palm Leaf Manuscript. The names of the bride and groom and that of their parents were originally written on a palm leaf, and included the date of marriage. Thereafter, the leaf is rolled and tied with a yellow string around the bride’s neck to resemble a “necklace” (Letchumanan 2022, Mangaiyarkarasi 2020).

Materials for Thali-making have evolved from using hunting spoils such as tiger claws, animal teeth and coconut shells (Ayur Pathar 2022), to copper and iron, ivory and agate, and gold, silver and gems.

Changes in Design and with Time

In the past, Thali designs were dictated by the regions from which the grooms came, i.e. the desert land (Palai), mountainous region (Kurinji), forest tracts (Mullai), the lower river valley (Marudam) and the littoral region (Neydal); and were respectively referred to as Maravar, Karuvar, Ayar, Ualar and Paradavar.

The designs were various and included the Perum Thali [2], Ciriya Thali[3], Tonkum Thali[4], Pottu Thali[5], Sanggu Thali, Rasey Thali, Thoopu Thali, Urandai Thali, Urandai Mani Thali, Kaarum Thali, Jagatha Thali and Irandu Thali (Arivukkarasu 2010). But these have since dwindled to four common designs (Nadesan 2022). The design of the Thali is selected by the groom’s family according to prevalent customs and the style worn by his mother. The various patterns and designs that are unique to a particular region and community reflect the continued practice of the caste, sub-caste and clan systems.

In Tamil communities, the brides’ Thali carries symbols of fertility and motifs of the sun, moon, Thiruneeru-Vibuthi , Thulsi plant, Shiva Linga[6] and the Goddess Meenakshi. There are also 3D Thalis filled with the resin, arraku, to keep their shapes. The Thali Thenna Poo Maram was largely worn by women from the Nadar and Marammeri castes. The Nadars were known cultivators of the palmyra trees and jaggery, and in coming to Malaysia, were involved in the toddy trade (Achariar 2016). The nature of their occupation and trade is reflected in the Thali’s design and motifs.

Meanwhile, the Pillayar Thali was worn by the Vellar clan; and the two-headed Pappar Thali was largely worn by the Pathar and Saiva Pillai clans, and features the masculine Shiva and feminine Shakti, or three horizontal lines symbolising the followers of Shaivism. Some members from the Vaishnavite Saiva Pillai and Brahmin clans also wore Thali with the motifs of Thulasi, Thulasi Madam and symbols associated with Lord Rama, such as sanggu, chakram or one vertical line with a “V” in between.

Selection of figures for the Thali is according to the regions from where the clan originates. In the Saiva Pillai Thali, for example, the figure of Lord Shiva is in mid-dance with one foot lifted, and the Goddess Madurai Meenakshi at his side[7]. In the past, women with such Thali were identified as belonging to the Madurai region and each year, on the month of Aadhi Perukku[8], these women would visit the Meenakshi temple to have the thread of their Thali replaced. This practice is unique to the region, but has been adopted by Malaysian Indians as well.

The Kazhuththu Uru is the Thali of choice for the Nattukottai Chettiars, a wealthy South Indian community of traders, merchants and moneylenders. The necklace is made of gold, a portion of which is gifted by the groom’s family to symbolise the union. Its main pendant Ethanam is surrounded by 35 smaller jewellery pieces, some featuring claw-like designs, that are made of sheet gold and strung on turmeric-smeared thread, complete with round and tubular beads. This particular Thali can easily weigh 20-30 gold paun.[9] The Thali of the Tamil Muslims is called Kariamani, which has at its centre a small gold rod.

During the wedding ceremony, the groom ties the necklace around the bride’s neck and forms three knots. However, in Tamil Muslim weddings, the fastening of the necklace, without the three knots, is done by close married female relatives[10] instead, after the names of the Prophet and his wives have been evoked. The Kariamani Thali is traditionally made by seven elderly married women.[11]

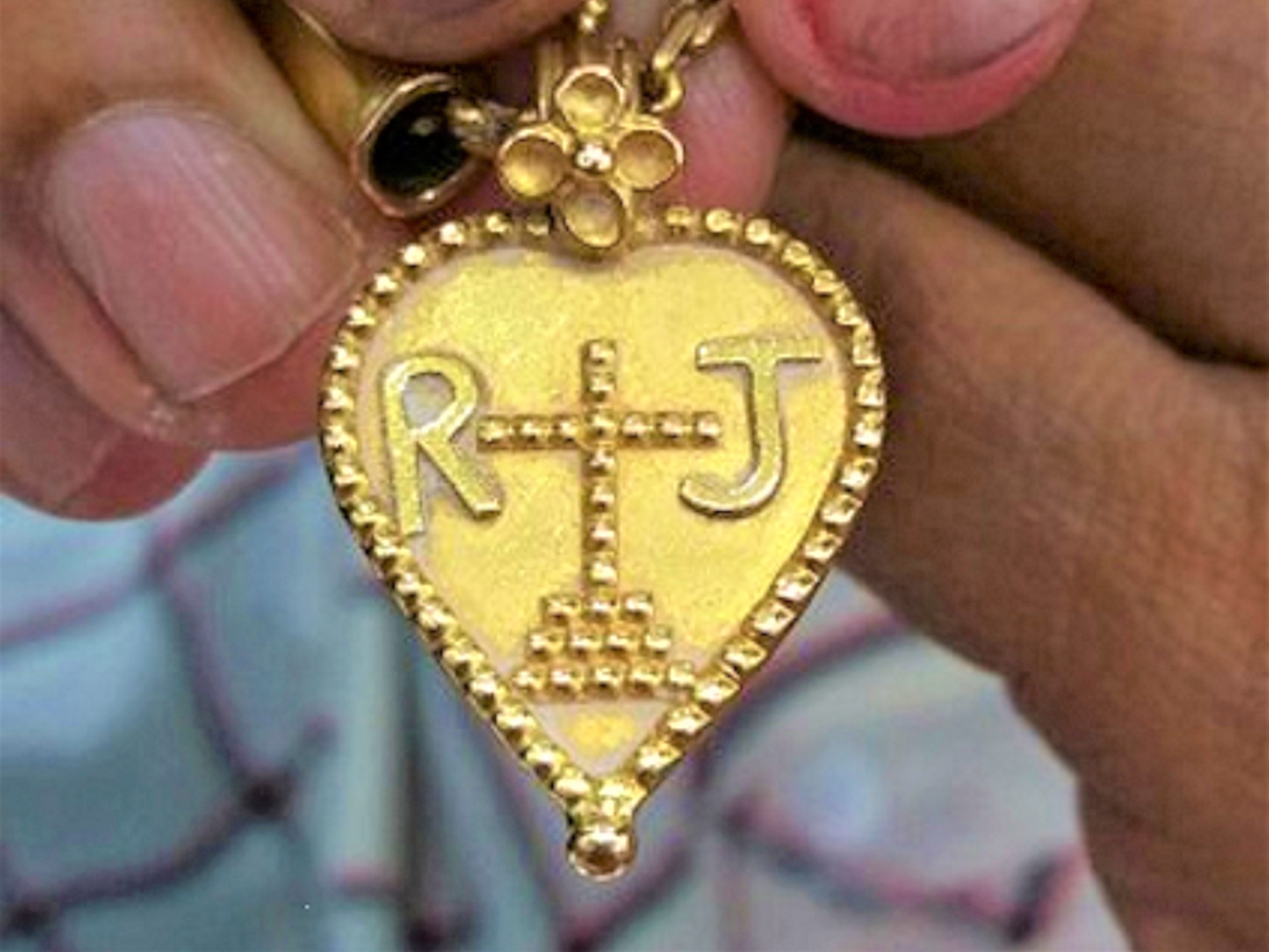

The Hindu Malayalees wear the Ela Thali; Ela denotes the leaf shape of a banyan tree. As for the Christian Malayalee Thali, the sign of the cross is engraved onto a solid gold piece which in Malayalam is called Minnu.

The Telugu Thali is similar to the Ramar Thali worn by women from Tamil Nadu. These women too wear the Pottu Thali, whose primary feature are two gold coins or discs, carved sometimes with South Indian designs, to represent the bride and groom. In the northern parts of India, the holy thread is strung with black- and gold-coloured beads. The gold beads represent the Goddess Parvati and the black ones, Lord Shiva. While the Gujaratis and Marwaris often use a diamond pendant for their wedding necklace.

For an Indian woman, the Thali is worn as a sacred thread of love and goodwill for her husband and for clan identification. On his passing, however, the Thali is cut and other adornments such as her bangles are broken and her toe ring removed. The widow must never wear these again. It is important to note that this custom is only reserved for deaths, and not for divorces.

All the same, the Thali-wearing tradition is changing with times. Youths today are choosing their Thali not based on caste and region identifications, but according to their personal tastes. The Indian diaspora especially are inclined to marry across castes, this therefore gives them the liberty to choose their preferred Thali types. Moreover, many are no longer in the same line of work as their forefathers, and feel that the Thalis are tenuous links in their representations.

But despite the changing trends and styles, the sacred symbolism of the Thali remains.

Footnotes:

[1] The silver jewellery worn by Seetha was designed and crafted by the people of Himachal Pradesh. In the ancient Hindu epics, this denotes an unbroken continuity of tradition from time immemorial to the present day.

[2] Largely worn by the Adi Dravida Clan, the Thali is huge and round-shaped (Nadesan 2022).

[3] Normally worn by the Nadar Clan, it consists of two small star-shaped Thali (Nadesan 2022).

[4] The Thali trend of today (Nadesan 2022).

[5] The design of this Thali is a round, inverted cup shape (Nadesan 2022).

[6] In Shaivism, this is an abstract representation of the Hindu god, Shiva.

[7] Madurai is also known as Velliambalam, where Lord Shiva was believed to switch his dancing position from the Natarajah pose upon the request of the Pandya king. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/madurai/street-talk-legendary-spot-where-shiva-changed-his-dance-posture/articleshow/38705134.cms

[8] The fourth month in the Tamil Calendar between July and August.

[9] Paun is a unit of mass that is commonly used in India's gold industry. While it is technically equal to 7.98805 grams, it is usually rounded off to 8 grams. In India, the pound sovereign was later shortened to just pound and then colloquialised further to pawan (also spelled pavan). In South India, it is largely called Savaram. Its use is now largely confined to conversations about precious metals and gold in particular.

[10] These close female relatives are usually the newlyweds’ mothers. In their absence, the elder or younger sister would take their place (Ibrahim 2022).

[11] The Indian Muslim community used to make the Thali chain with 21 wheat-shaped gold beads, along with the Kariamani. Later, the seven elderly married women in the family would string these together on the day before the wedding. The practice has changed over the years (Nadesan 2022).

Preveena Balakrishnan

specialises in ethnoscapes and intangible cultural heritage valuations.