The Japanese Conquest of Penang: Part One

By William Tham, Enzo Sim

THE OVERWHELMING FOCUS on the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 19411 as the start of the Pacific War means that the actual first shot is largely forgotten – that was fired on the shores of Kota Bharu, Kelantan, where the Japanese Imperial Army had landed just slightly over an hour earlier, while their airborne counterparts were still en route to Hawai’i.2

Japan’s grand plan to unify East Asia, beyond occupied Korea and the eastern parts of China, was accelerating. Its expansionist ideology, espoused by radical nationalists, took root in the 1930s and found its full form in what Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka formally termed the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” in 1940. Japanese propaganda described how Japan sought to free Asian countries from Western colonialism before unifying them, whereupon Asian countries would live in co-prosperity under Japanese leadership.3

With oil embargoes imposed on the export of petroleum and materiel to Japan by China’s Western allies, aimed at crippling its military operations in China, breaking the Western embargo by expanding across Southeast Asia and exploiting its natural resources became necessary.4

On the anniversary of the onset of the Pacific War, 80 years ago this month (December), Penang Monthly looks back at the invasion and its legacy in Malaya in a two-part article.

The Broader Picture

After much deliberation, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s Kuomintang (KMT) government finally, and decisively, turned away from an alliance with the Fascist powers, including abandoning its relationship with the Wehrmacht of the Third Reich, following the Xi’an Incident in 1936, which saw him being taken hostage. The KMT reluctantly agreed to a united effort with what Chiang regarded as the main enemy, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), to resist Japanese aggression which had enveloped swaths of China.5

With that, the KMT was able to tap into a deep stream of anti-imperialist and anti-Japanese sentiment in Malaya, with roots dating back to the May Fourth Incident of 1919. This atmosphere was largely created and sustained by the political left, which ensured that by the eve of war, the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), independent of the Yan’an-based CCP, “remained the only political organization capable of assisting the British in the defence of Malaya or of going [at] it alone in the war of resistance against the invading Japanese.”6 Demonstrations, boycotts and occasional riots drew mass participation, such as the “Soya Beans” Affair in Penang in July 1938, during which Japanese grains and other goods were seized and destroyed.7

The Japanese were already active in Malaya at this time, and military intelligence from its shores and other future colonies was being conveyed to the Taiwan-based Japanese Military Affairs Bureau Unit 82 by secret agents – Japanese embassy staff, disaffected Malayans, Japanese and Taiwanese “merchants” who operated businesses such as dental clinics and photography studios, as well as “tourists”. These agents also included British army officers such as Captain Patrick Stanley Vaughan Heenan, whose betrayal saw the destruction of much of the Allied air force in Malaya, and the aristocrat Lord Sempill.8

The Japanese also reached out seriously to local nationalist movements, such as Ibrahim Haji Yaacob’s Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM), which became linked to the pro-Japanese Indian nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose through the efforts of military intelligence officers such as Iwaichi Fujiwara.9 Japanese-occupied Hainan Island and French Indochina were outfitted as staging areas,10 thus setting the broader stage for what was to come.

The Pincer

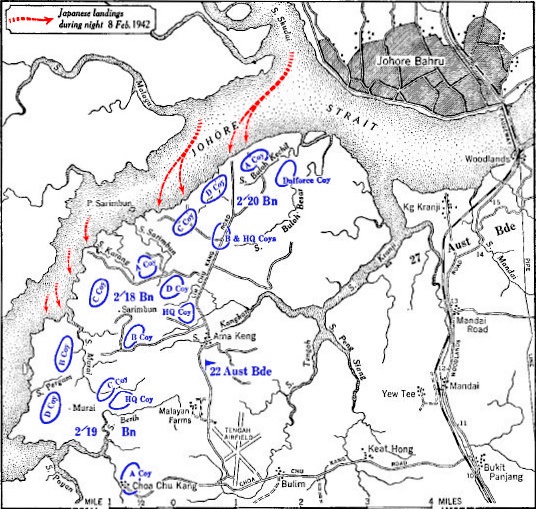

The Japanese 25th Army, under General Yamashita Tomoyuki, began their advance on December 8.11 Despite the gallantry of the British Indian Army, which utilised pill boxes and trenches to pin down the landing party at Kota Bharu, the Japanese 18th Division advanced deep into the Malayan heartland within a day of their landing. They split into separate groups: one headed towards Kuantan while another rushed towards Perak.

Around the same time, the 5th Division crossed the Siamese border and defeated the 11th Indian Division at the incomplete defences of Jitra.12 The lines, mainly held by the British Indian Army, the British Army and Commonwealth troops, swiftly collapsed in northern Malaya, especially after the Japanese gained air supremacy there. This was aided by the sinking of multiple warships of Force Z, which included the storied Prince of Wales and the Repulse. Just one day after the invasion began, the Japanese were already launching air raids on Penang.13

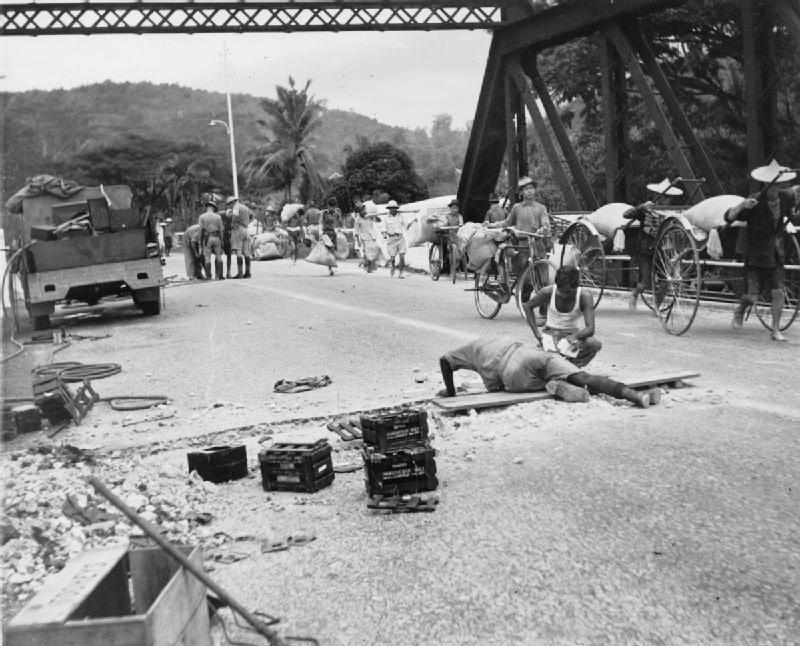

At 7am, air raid sirens were heard for the first time as eight Japanese bombers launched their first airstrike on Bayan Lepas Airport. The Butterworth Airbase and the nearby oil tanks were devastated with antipersonnel and fragmentation bombs, forcing the airbase’s final withdrawal on December 15. But even four days before the abandonment, residual Allied air defence in Penang had already been effectively eliminated, which allowed bombers to dive-bomb George Town in three successive waves before machine-gunning civilians, leaving behind piles of dead bodies and burning buildings as civil servants and policemen fled, allowing looters to roam freely. This situation prompted waves of civilians to flee to Air Itam and Penang Hill, where the extended families of local bungalow caretakers found refuge during the Occupation.14

Penang Abandoned

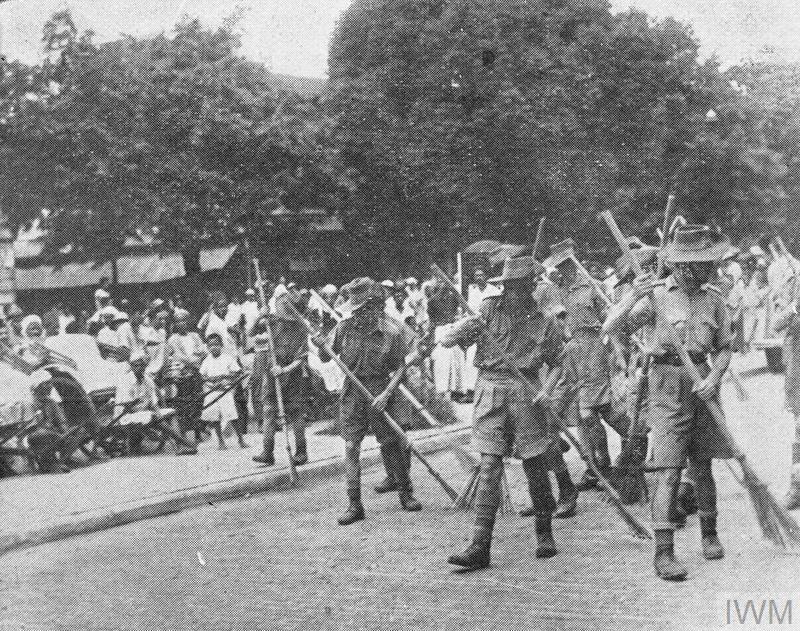

By December 15, the last British and Commonwealth troops destroyed and abandoned the Batu Maung Fort, the evacuation of European residents from Penang having already been completed. These residents had been ferried from the lobby of the Eastern and Oriental Hotel to the mainland, and then towards Singapore.

Despite being offered the chance to be evacuated together with the Europeans, none of the local Penang and Province Wellesley Volunteer Corps members, except for one, took up the offer, because the evacuation of their family members was not guaranteed by the British. This act of racial discrimination was later seen as one of the empire’s cruelest betrayals.15

Finding themselves abandoned, a group of civil society leaders gathered on December 18 to establish the Penang Service Committee, under the leadership of the Ceylon-born editor of The Straits Echo, Manicasothy Saravanamuttu. They immediately decided that the Committee’s first task was to take down the Union Jack, still flying at the Esplanade, to signify the Island’s abandonment. On top of that, the Committee also freed Japanese civilians, getting them to write messages on large pieces of cloth which would be raised at the Esplanade.

Perhaps the most remarkable of Saravanamuttu’s selfless acts that day was commandeering the only radio station in Penang, over which he appealed to the Japanese:

“This is Penang calling. Penang calling the Japanese Headquarters in North Malaya. Penang has been evacuated by the British. There are no more troops or any defences whatsoever in Penang. Please refrain from bombing Penang.”16

The arriving Kobayashi Battalion, taking control of the open city, began rounding up teenagers residing in makeshift squatter camps in Air Itam before forcing them to march towards the prison. They were interned until their relatives could secure their release. Yamashita had to personally step in to stop incidents of rape occurring in the colony. And the radio station, which earlier on channelled Saravanamuttu’s appeal, saw a new message being directed at the British headquarters in the south:

“Hello, Singapore, this is Penang calling. How do you like our bombing?”17

Read Part Two here: https://penangmonthly.com/article/20533/the-japanese-conquest-of-penang-part-two

William Tham

His novel, The Last Days, is set in 1981 and covers the continuing legacy of the Malayan Emergency. He is currently an editor-at-large with Wasifiri and also an MA candidate at Universiti Malaya.

Enzo Sim

is a Mass Communications graduate who has an unwavering passion towards international relations, history and regional affairs of Southeast Asia. His passion has brought him to different Southeast Asian capitals to explore the diverse cultural intricacies within the region.