Anecdotal Accounts of Chinese Women Migrants to Southeast Asia

By Dr. Kuah Li Feng

In Penang Monthly’s Campbell Street-themed issue, we explored how the street gained infamy as a prostitution hub (see August 2021, A Red-light District Worthy of a Vibrant Port). This next feature documents the stories of some of the women, and how they were either sold or tricked into the trade.

---

“I finally reached Singapore after seven days and seven nights at sea. The port was crowded with people when the ship moored. Among them were ‘white people’ with blue eyes and yellow hair, ‘black people’ with white teeth and dark skin. There were also ‘yellow people’ like myself. My eyes were dazzled, but every nerve-ending in my body crackled with tension. This new and strange environment disorients me, and in a panicked daze, I follow the rest, setting foot in the port of Singapore for the first time.” Source: 廖冰 (1996), p.229

THE PASSAGE IS an English translation of an anecdotal account that captures in vivid detail the feeling of fear and panic of a Chinese woman migrant newly arrived to Southeast Asia in 1930. There was a great influx of Chinese immigrants to the region from the late 19th to the 20th centuries.

According to scholar Fan Ruo Lan (范若兰), the journey from China to Singapore and Malaya before the 1940s was for a woman migrant, physically challenging and replete with unknown threats. She would first have to travel from her inland home village to the nearest treaty port, for example, Hong Kong or Amoy. From there, a ship ticket would be purchased to the Straits Settlements, which could take anywhere between five to eight days to reach.

Upon arrival and for the purpose of disease control, she had to be quarantined for a few days. In Penang, this was done at Pulau Jerejak. Once in the clear, the woman would be interviewed by an inspector attached to the Chinese Protectorate that monitored the illegal trafficking of women and children, before entry into the colony was permitted. For many, this marked the beginning of yet another unknown fate and future.

Fan Ruo Lan gives three reasons behind the emigration trend: 1) As dependents, these women either migrated with their husbands and / or families, or they travelled abroad to join their spouses and / or relatives; 2) As independents, women who chose to migrate of their own will and volition for a better livelihood; and 3) Forced, women and young girls were sold by their families, or tricked and abducted by human traffickers.

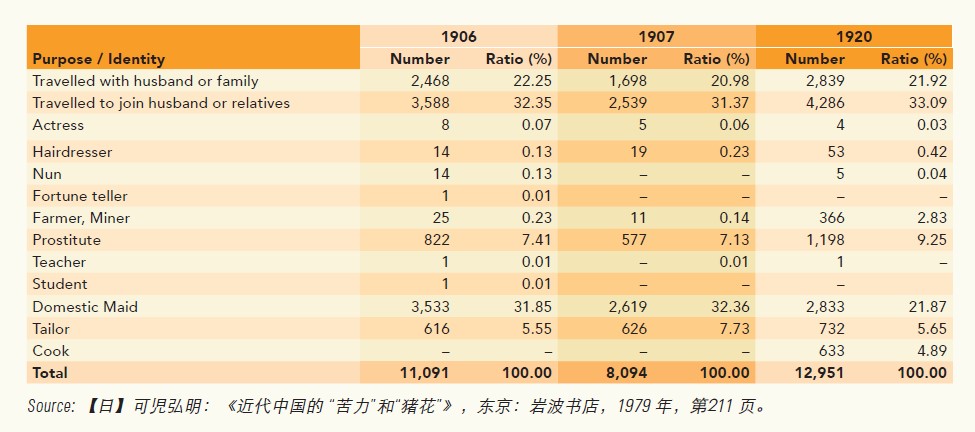

In comparing Fan Ruo Lan’s findings with the statistics compiled by Japanese scholar Kani Hiroaki from various government reports, 50% or so women emigrating from China in the early 20th century for family reasons projected a rather “safe impression” overall. Around 40% came for work, as domestic maids, prostitutes, tailors, farmers and miners, etc.

But autobiographies such as Lim’s (1958) offer glimpses into realities that are missing from the official records. Lim came to Singapore in 1932, at the age of eight:

The woman said to me before we went ashore, “Remember what I told you before!” I replied, “Yes, I remember. I must tell anyone who asks me that this woman is my aunt.”

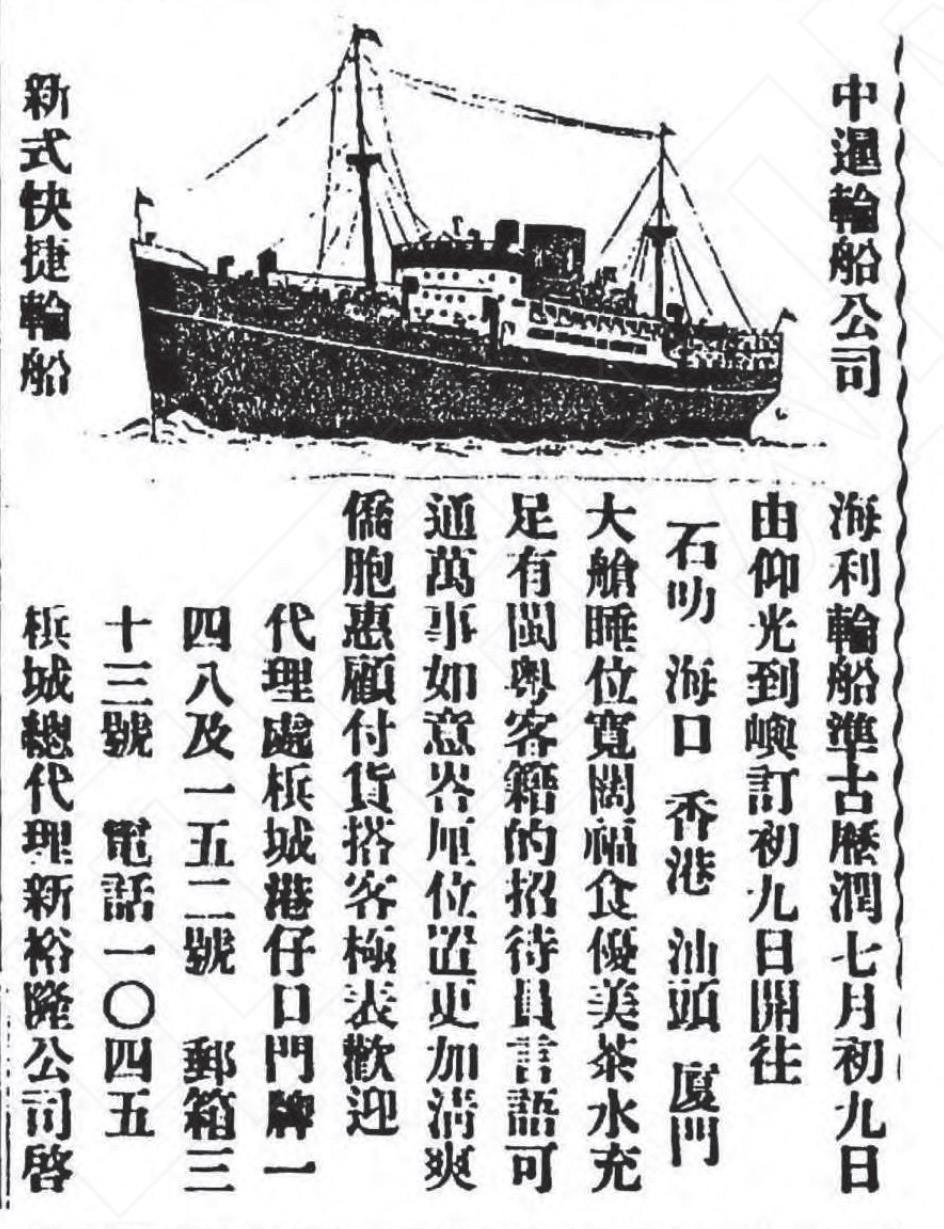

An advertisement of a Penang ticketing agent. In 1934, to attract more women passengers to Singapore from Hong Kong, a ticket cost 30 dollars. Returning male migrants were also charged the same fee, but this doubled to 60 dollars for new male migrants. Source: Penang Sin Pao, September 7, 1938.

Lim remembered the woman had with her five girls and two boys, all of whom passed the entry investigations successfully. The girls were sold; in fact, Lim herself was sold for 250 dollars to a Chinese family as a mui chai (domestic maid). Lim’s story does somewhat throw a curveball at the validity of Hiroaki’s data; of the 50% or so women who claimed to have come over for familial reasons, there was a high possibility that many of them had been coerced to lie.

Indeed, from the late 19th century, concerns over the trafficking of women and children began to unsettle the local Chinese communities. The Penang Sin Poe reported in 1896:

中国海禁打开,耻徒往往拐诱良家妇女带到海外,充 当佣妓,广东此风最盛。。。

With the opening of treaty ports in China, innocent women are cheated by outlaws and sold overseas as maids and prostitutes. This is most serious in the Canton area … (translation)

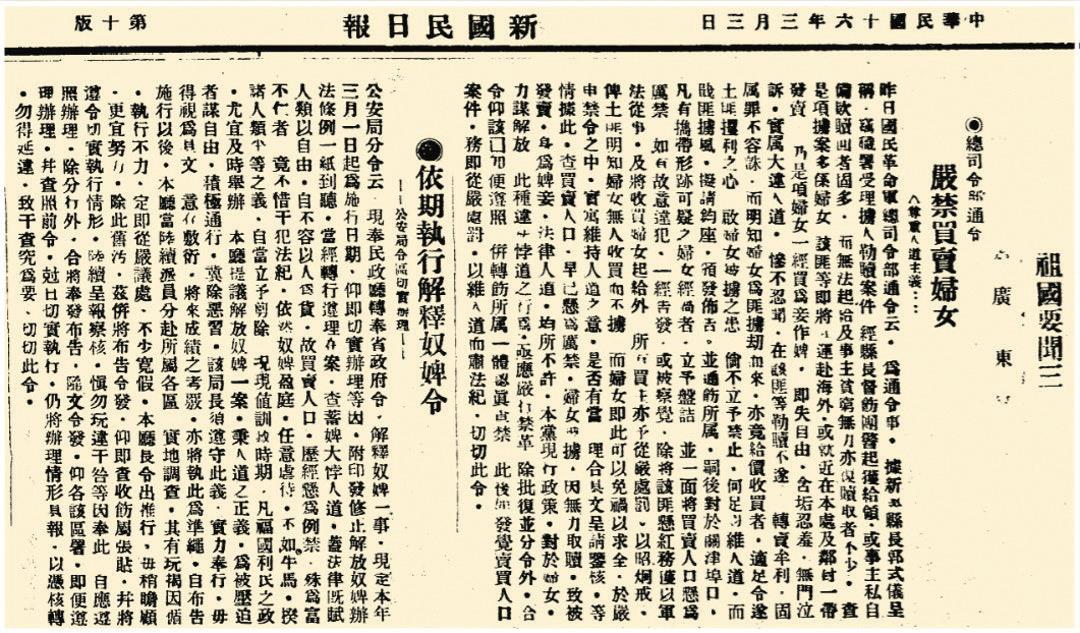

The Singapore-based newspaper Sin Kuo Min also reported on the seriousness of the issue by republishing from a Chinese newspaper the 1927 article, Prohibit Trafficking of Women. Vulnerable children were not spared either.

A letter issued by the Hong Kong Poh Leong Kuk in 1891 shared that a common trick among the syndicates was to adopt children from orphanages. Alternatively, they’d wait outside the foundling homes and beg approaching families to give or sell them their infant girls. It was discovered through investigation that once these girls were adopted, the syndicates would raise them for a few months or sometimes even years before shipping them overseas for sale. Buyers on the other side would “care” for these girls until the age of 14 or 15, before selling them to brothels.

According to Jean (2011), an estimated 80% of the women and girls who came from China in the late 1870s were sold into prostitution in Singapore, then the epicentre of human trafficking. From there, girls were bought and sent to various parts of the region. In Penang, they were sent to Campbell Street, Penang’s red-light district of the day.

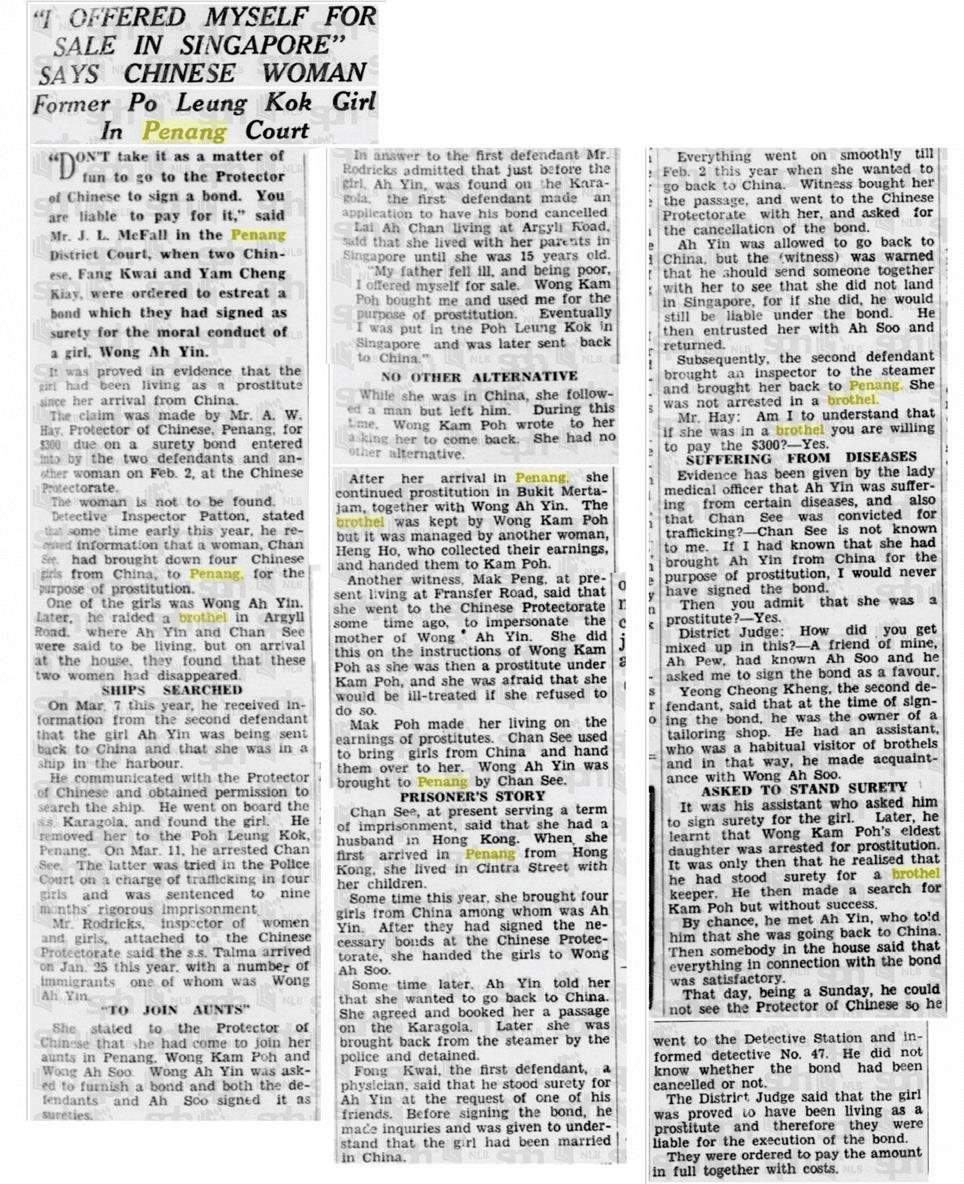

The news clipping from The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (right) provides a glimpse into an established regional network and operation of human trafficking activities, spanning two generations of Chinese prostitution in Penang.

Read Part Two here: https://penangmonthly.com/article/20549/prostitutes-in-penang-a-life-often-filled-with-fear-and-violence

Dr. Kuah Li Feng

is an ethnographer and cultural

practitioner. She founded Studio Good Think in 2011, one of the first private heritage service consultancies in Penang focusing on cultural research and interpretation.