Covid-19 Exclusives: Wu Lien-Teh: The Malayan who “Squashed the Curve” of the 1910 Pneumonic Plague

By Liew Chin Tong

FEATURE

You read it here first! Our Covid-19 online exclusives.

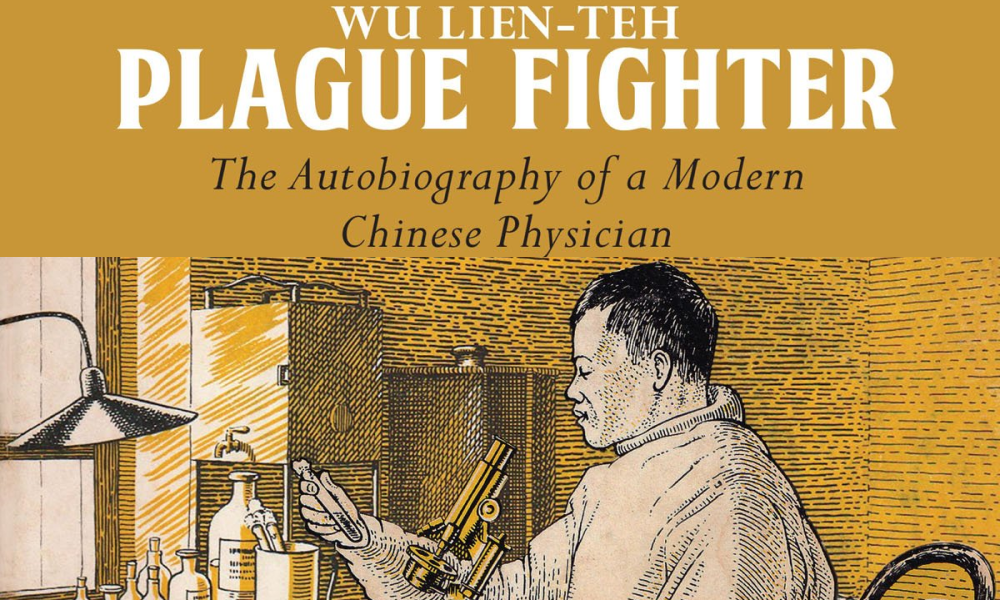

ON THE OCCASION of World Book Day 2020, when the world is locked inside their homes to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus, it is apt that we take some time to remember an oft-forgotten character – Dr. Wu Lien-Teh (1879-1960), and revisit his fascinating autobiography Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician.

One day not long ago, as I was jogging in a park, I spotted the words "Wu Lien-Teh" on someone’s t-shirt. I thought my eyes were playing tricks on me, because I had just been reading the book. As it turned out, it was a student from Penang Free School wearing the school’s official jersey for the sports house named after Wu Lien-Teh.

When I was running Penang Institute (2009-2012), civil society activist Datuk Anwar Fazal arranged a visit by a group of Wu Lien-Teh researchers and enthusiasts from China to discuss promoting research and commemorative activities in Penang. Scholars in China had recently “rediscovered” the significance of Wu Lien-Teh’s medical contributions after SARS in 2003.

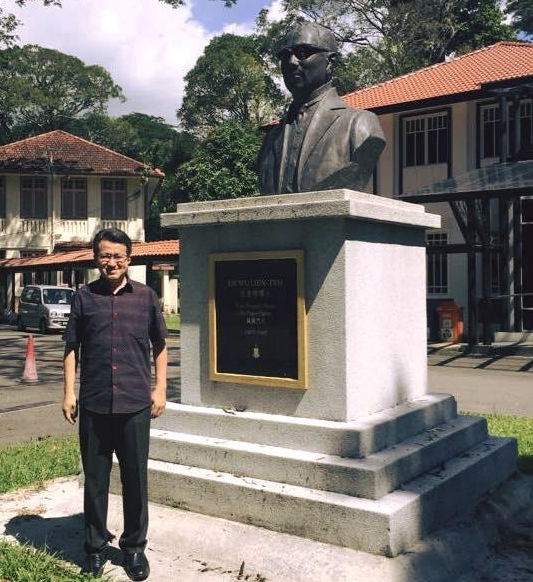

I was glad to hear that after I left Penang, the Wu Lien-Teh Society was established, headed by Anwar Fazal. Since Penang Institute functions as its secretariat, a bronze statue of Wu Lien-Teh, a gift from China, was installed on its grounds at No. 10-12 Jalan Brown to commemorate the life of one of Penang's most illustrious sons.

In 2014 The Star sponsored Areca Books to do a reprint of Wu Lien-Teh’s 660-page autobiography. Over the years, I must have purchased at least 20 copies of it as gifts for friends.

Now, re-reading this book against the backdrop of the current pandemic is indeed profound and sobering.

To some extent, the current crisis is more severe than the Manchurian Pneumonic Plague of 1910-11 which Wu Lien-Teh faced. Wu arrived in Manchuria only in late December 1910, going up from Tianjin where he had been teaching since 1908. As testimony to his hard work, by March 1, 1911, there were no more new infections being reported. The entire month of April 1911 was then devoted to an International Plague Conference organised by Imperial China, with Wu as the conference’s president.

The epidemic management and control models he pioneered (masks, contact tracing, quarantine, social distancing, movement control, etc.) remain strikingly relevant to us today.

Wu designed a mask using layers of cotton and gauze which was the precursor to the modern surgical mask. After encountering initial scepticism, Wu's mask was widely reproduced since it was cheap, easy to produce, and effective in countering the spread of the disease.

What’s more, just the other day, I read that India uses train wagons as quarantine wards. Wu was the first to have done so, a 110 years ago. He also made use of policemen and soldiers for “contact tracing”.

On March 20, I wrote that until we have a reliable vaccine for Covid-19, mask use will inevitably be an important part of the fight against the virus. A month ago, the World Health Organization and many governments were still saying that masks were not needed for people without symptoms. My own view was somewhat influenced by Wu Lien-Teh's example.

In one of the cases illustrated by Wu in his book, there was a Dr. Hsu who was very careful and always wore a protective mask. Sadly, a simple accidental exposure to a sick attendant cost him his life. One day, he was in the office of the Chief Medical Officer, along with a few others. He found that the tea was cold. “Dr. Hsu reproved the servant, who turned round and replied with some heat that fresh hot water was not ready. Probably at that moment some sputum was ejected from the servant’s mouth.” The servant died of plague that evening, while Dr. Hsu died several days later.

Granted, we are talking about different diseases 110 years apart. But still the lessons to be learned are similar.

The wild animal trade in China caused the plague in 1911, just as it is deemed to have caused the present pandemic. Traditionally, experienced hunters of tarabagan, a type of marmot, would only hunt the healthy ones. But as the demand increased for marmot skins in Europe and the US in the years leading up to the plague, many inexperienced hunters joined the trade and were killing the animals indiscriminately, and food being scarce, they often cut up, cooked and ate the flesh of the marmot. These seasonal hunters had crowded lodgings in cheap inns, and 20-40 people would stay together in badly ventilated rooms to survive the cold Manchuria winter.

The plague was being transmitted through the new train systems, most parts of which were less than a decade old then, to the towns that the railway lines connected, eventually killing 60,000 people.

In 2020, the disease is transmitted by air travels.

The book is also fascinating for two other reasons. The first is about Wu and Penang at the turn of the 20th century.

Wu provided a Malayan illustration of life in Penang around the turn to the 20th century. This is significant because most accounts of that period were written by Europeans.

Wu was a top student at Penang Free School and won a scholarship to Cambridge in 1896. Upon his return to Malaya, he devoted a year to the Institute for Medical Research (IMR) in KL in 1903-1904. This institute is still around today; and in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis, one lesson we should learn is that much more money should be allocated to medical research outfits such as this. Perhaps IMR can consider honouring Wu Lien-Teh as one of its non-European pioneers.

Life in Penang between 1904 and 1908 was tough, and Wu’s social activist stance, particularly his anti-Opium campaigns, pitted him against the colonial authorities and left him forever feeling bitter about them. Wu is linked by marriage to Dr. Lim Boon-Keng, a famous Straits Chinese leader in Singapore. Their wives were daughters of Huang Nai-Siong, the Foochow Methodist pioneer who brought migrants to Sibu.

The second reason relates to Wu and the turbulence in China (1908-1937).

No other Malayan was as intimately connected as he was to the changes in China from around the time of the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 till his return to Malaya after the Japanese invasion of China in 1937. For someone who did not read Chinese and barely spoke the northern/Peking dialect (Wu spoke Cantonese), it was a miracle that he thrived for over 20 years in Chinese official circles as one of the highest ranked medical officers.

Just when he arrived in China in 1908 and was about to head to Beijing, Emperor Guang Xu was announced to have passed away and within 24 hours Empress Dowager was also dead. Until the end of their lives, Wu remained a personal friend of Tang Shaoyi (唐绍仪), the man who in 1912 became the first premier of the republican government. Wu was also a close friend of London Times correspondent Dr. George Ernest Morrison, the father of Ian Morrison, the Times journalist who died in the Korean War – the character Han Su-Yin wrote about in Love is a Many-Splendored Thing.

The English-educated Wu gave Trinidad-born Chinese Eugene Acham his Chinese name Chen You Ren 陈友仁 following their encounter on a long train trip. Chen rose to become a short-lived Foreign Minister of China. Wu attended to “Emperor” Yuan Shikai (袁世凯) as one of his doctors towards the end of the latter’s life, and was appointed “Physician Extraordinary” to the President who succeeded Yuan.

To a student of history, Wu’s life provides fascinating and rich details about a dramatic and turbulent period in China and the region.

To conclude, I hope more people will read the story of Wu Lien-Teh in order to understand and emulate the adventurous spirit that saw a Malayan contributing so significantly to the world. Wu was in fact nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1935.

Needless to say, we have much to learn about epidemic prevention from the man who modernised China's health care system.

Liew Chin Tong

is a Senator and Member of Penang Institute’s Board of Directors.